Banner image: Ladys Fingers

“My art is what I’m doing while I’m trying to work out what I’m doing.”

Visual Improvisation and the Polymath’s Eye

Emerging from the cultural ferment of 1960s England and educated in the radical Fine Art department of Leeds Polytechnic during the 1970s, John Sherwood has cultivated a practice that thrives on curiosity, spontaneity, and boundary-breaking. Living and working in Skipton, North Yorkshire, Sherwood is a self-proclaimed polymath whose artistic range spans collage, painting, writing, sound recording, and digital media. His multifaceted output is unified by a signature approach: the ‘Amalgam’—a form that synthesises image, text, and gesture in a layered and exploratory way. These Amalgams resist tidy categorisation, instead revealing themselves as visual arenas where diverse influences, materials, and memories intersect.

Sherwood’s background in Western painting has remained a foundational anchor, but he draws inspiration from sources far beyond the gallery wall. His practice is informed as much by machinery, cave art, and Stone Age flint tools as it is by the pages of glossy magazines or the structure of a wedding cake. His openness to eclectic inputs is not merely aesthetic but ideological; he believes that creativity lies in accepting whatever arises—accident, impulse, or fragment—and allowing it to contribute meaningfully to the work. His studio, affectionately dubbed the “Playroom”, reflects this approach: a compact but densely packed creative space that holds not only traditional art supplies but also crates of unorthodox materials, digital devices, and stacks of reference material collected from music, video, and everyday encounters.

In addition to his expansive artistic output, Sherwood also works through a series of performative alter egos, the most prominent being Eric Bloodorange—an enigmatic, comedic persona whose name emerged from Sherwood’s wordplay on the Viking warrior king, Eric Bloodaxe. Eric Bloodorange writes poetry, paints, and occasionally appears on stage delivering idiosyncratic scripts to live audiences. He is accompanied in this imaginative theatre by a cast of equally distinctive characters, including Dr Strabismoo, Sid Satsuma, and Timmy Tangerine. These invented personalities are not peripheral quirks but integral to Sherwood’s creative ecosystem: they allow him to channel different voices, moods, and forms of expression that might otherwise remain latent. Through them, Sherwood explores absurdity, satire, and surreal humour—reinforcing his commitment to dissolving boundaries between art forms, identities, and states of mind.

By resisting fixed methods and welcoming interdisciplinary flow, Sherwood has built a unique artistic identity that mirrors his philosophy: that art should function as a continuous monologue—or more accurately, a dialogue—between the maker and the ever-shifting visual field. For Sherwood, the act of creation is not about reaching a finalised image, but about navigating a process in which intuition leads, and understanding follows. It is this open-endedness that gives his work its distinctive character: layered, unpredictable, and alive with the rhythms of both thought and play.

Travellers

John Sherwood: A Legacy Rooted in Influence

Rather than distancing himself from artistic forebears, Sherwood embraces influence as a vital component of his process. His creative lineage includes modernist visionaries, experimental polymaths, and historical masters. From the collaged symbolism of Alan Davie to the raw spontaneity of Outsider Art, Sherwood finds connection with figures who have questioned convention and invited multiplicity into their work. The impact of Jean Dubuffet’s emphasis on material qualities over colour, and the visual clairvoyance achieved through ‘drawing stupidly’, resonates strongly with Sherwood’s approach to his Amalgams. Likewise, Surrealism’s irrational logic, as championed by Max Ernst and the broader Dada movement, is visible in his embrace of juxtaposition, automatism, and the unconscious.

Sherwood’s affinity for artists who span disciplines reflects his own artistic philosophy. Man Ray’s stylistic fluidity and Marcel Duchamp’s conceptual audacity both affirm Sherwood’s belief in crossing boundaries. He sees Duchamp as an innovator of equal—if not greater—magnitude than Picasso, whom he nonetheless deeply admires for fracturing the structure of Western art. The performative introspection of Frida Kahlo has given Sherwood permission to work autobiographically, while William Blake’s integration of image and text—anchored by a defiant visionary spirit—has encouraged Sherwood to explore the interstices of word and image within his own compositions.

Sherwood’s admiration also extends to polymaths outside the traditional fine art canon. He cites cultural mavericks such as John Lennon, Ivor Cutler, Captain Beefheart, and Yoko Ono as affirming his belief that art can—and should—spill across media and disciplines. These figures, often working across sound, literature, and performance, embody the fluidity that Sherwood himself practices. In his view, they provide the ‘green light’ to do the same—to live and create at the intersection of all these influences without the need for rigid separation. That creative sanction underpins the entire ethos of the Amalgams, which he sees not only as artworks but as expressions of a life lived through process, perception, and participation.

Doodlesque

The Amalgams as Continuum and Container

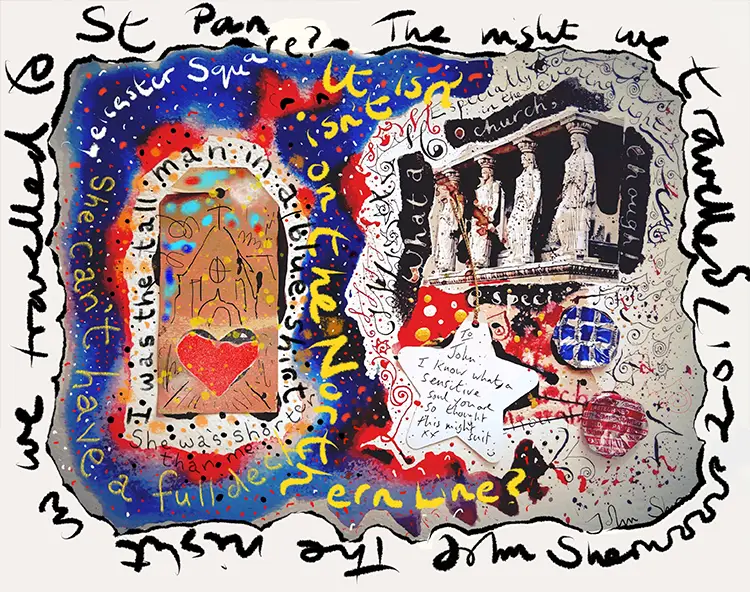

Sherwood’s most recognisable body of work, the Amalgams, function as evolving documents of his artistic journey. These pieces often blend drawing, collage, hand-printed words, digital elements, and calligraphic flourishes, creating layered visual fields that feel more like ongoing conversations than finished compositions. The Amalgams are inherently inclusive: they gather mistakes, spontaneous marks, and half-formed thoughts, granting them equal weight alongside more ‘deliberate’ elements. This openness reflects Sherwood’s belief that art is less about perfection and more about process. Each Amalgam becomes a kind of snapshot of the artist’s internal and external environments at the moment of making—whether it’s a scrap from a video transcription, a lyric, or a doodle inspired by his music collection.

Certain Amalgams stand out within this extensive practice. Lady’s Fingers has distinguished itself as an exceptional example, embodying the qualities Sherwood values most: unpredictability, coherence in disparity, and the sense that something intangible has aligned. Similarly, Force Crag Mine Switch marked a breakthrough in his confidence with oil painting, while Doodlesque further affirmed his intuitive process. His 60 by 45s series, comprising around three hundred Amalgams, represents a landmark in his output—one he describes as a “peak” of creative achievement. Another deeply resonant project is the Pandemic Amalgam Diary, which captures the atmosphere, anxieties, and reflections of the COVID-19 era through the same spontaneous and multifaceted lens.

While he dreams of eventually housing his entire oeuvre in a single dedicated space—perhaps a “John Sherwood Art Museum”—he is also pragmatic. He acknowledges that the global distribution of individual pieces is both necessary and inevitable. Still, the desire to present the work holistically reflects the interconnected nature of his practice. Each piece may function independently, but their true power, he suggests, lies in how they resonate with one another. The Amalgams are not isolated statements; they are fragments of a larger, ever-unfolding narrative that reveals its richness when experienced in constellation.

The Night We Travelled to St Pancras

John Sherwood: Mapping the Inner Monologue

Sherwood’s artistic style resists neat classification because it is driven not by formal technique or thematic agenda, but by openness to encounter. He draws on the idea that the artwork itself determines its form, with the artist acting as a kind of conduit. This results in a visual language that is both spontaneous and deeply personal, with each composition reflecting his internal landscape at a given moment. He quotes Paul Klee’s assertion, “I am my style,” to articulate this alignment between self and work. Rather than striving for a uniform aesthetic, Sherwood lets the work evolve organically, guided by what he describes as an unfolding monologue—a dialogue, even—between himself, the pictorial space, and sometimes the eccentric voices of his alter egos.

His journey as an artist began in early childhood, when his father—a schoolteacher—brought home sheets of plain paper. This simple gesture seeded a lifelong practice. He later refined his vision at art college, but the instinct to make art came first and has always been rooted in personal need. The influence of those early years in Melton Mowbray, as well as the broader cultural impact of the 1960s, played a formative role. Music, countercultural ideas, and evolving attitudes towards art all became part of his creative DNA. While his work has grown in complexity over the decades, its emotional core remains constant: a response to life’s contradictions, confusions, and questions.

Even his choice of medium is personal and rooted in memory. A childhood encounter with a mapping pen and Indian ink—courtesy of his father—sparked a lifelong affinity for the dip pen, which remains one of his preferred tools. These early experiments in line and flourish have evolved into a hallmark of his Amalgams, where handwritten text and spontaneous doodles coexist with other visual elements. For Sherwood, this process is devotional. He compares the artist’s life to that of a monk, engaged in a daily practice of responding to the human condition. The art becomes a kind of slipstream left in time’s wake: a trace of what it means to think, feel, and create in an unpredictable world.