Silent Guardians and Sacred Wood: Foundations in Nara

Growing up amid the spiritual stillness of Nara, Kouta Sasai absorbed more than just visual inspiration—he inherited a reverence for presence and time. His early encounters with Japan’s ancient artistry, particularly the formidable wooden sculptures of Unkei housed in the Shin-Yakushi Temple, ignited a profound connection to form and silence. These monumental guardian figures, carved with both intensity and devotion, did more than impress him—they awakened an understanding that art could be both a container for, and a conduit of, something beyond the tangible. Sasai has often reflected on how these sculptures seemed not simply to exist but to reside, carrying centuries of quiet authority in their grain. This early proximity to sacred craftsmanship formed a bedrock that continues to influence his painting—anchoring it in questions of existence and memory.

His formal education at Hiroshima City University further deepened that inquiry, guided by painter Hiroshi Noda, who emphasized authenticity and depth over technical perfection. Noda’s mentorship encouraged Sasai to observe beyond the visible and to regard painting as a slow excavation rather than a performance of skill. Sasai’s studies led him to confront the habitual mechanisms of image-making, pushing him to let go of formulaic approaches in favor of something more instinctive and vulnerable. The moment his work was selected for the university’s permanent collection marked an early validation, but it was the quieter, personal discoveries in the studio that truly shaped his direction. By the time he completed his master’s degree, Sasai had begun to identify painting as a process of returning—of continuously circling back to a question rather than offering answers.

This circular motion found fertile ground in the places he chose to live and work. In Miyajima, Sasai immersed himself in the slow rhythms of a wooden townhouse surrounded by nature and history. The silence of the island, its deer-filled streets and lapping shores, mirrored the inward quietude he sought in painting. Later, relocating to Fukushima introduced a different atmosphere—one tinged with reflection and sobriety. Both environments shaped the emotional temperature of his work, not by dictating content but by coloring the spaces in which the paintings emerged. Sasai allowed these surroundings to seep into the brushstrokes, treating his studio not as a sealed-off space but as a resonant chamber where the outside world subtly leaves its imprint.

Kouta Sasai: The Unseen Weight of Memory

Sasai’s artistic inquiry orbits around themes that resist containment—memory, shadow, impermanence—all of which elude precise definition but press insistently on the psyche. He approaches painting not as a means to depict, but to evoke; not to explain, but to trace the outlines of what lingers at the edge of perception. Memory, in his view, is inherently unstable—distorted and elusive—yet undeniably formative. It shifts in texture and clarity, like a shadow that moves across a wall, never fully fixed. Sasai’s canvases engage this instability, leaning into ambiguity rather than resolving it. The act of painting becomes a search for presence in the absence of certainty—a quiet grappling with the ephemerality of lived experience.

The shadow, for Sasai, is not merely a visual motif but a philosophical tool. It is absence shaped by form, presence defined by what it obscures. In his series Perpetual Shadow, which has been exhibited several times in Tokyo, this concept is rendered not as symbol but as structure. The works are not anchored to narrative or fixed meaning; instead, they present thresholds—moments suspended between clarity and dissolution. The shadow functions as a guide, not to lead the viewer into darkness, but to mark the passage where inner and outer landscapes converge. Through this series, Sasai revisits the same question repeatedly: what remains when form begins to fall away?

Reaching the psychological state necessary to create these works is a discipline of relinquishment. Sasai describes his process as one of deliberate forgetting—moving past technical training and conceptual planning to arrive at something more instinctual. He begins with drawing, sometimes methodically, other times in bursts, then layers paint until the canvas starts to speak back. In his most resonant moments, he is no longer the painter, but a witness. The painting begins to assert its own will, breathing independently of his direction. This surrender is not about passivity but about accessing a deeper current—a place where the self recedes and something unnamed begins to surface.

Chiseling Flesh and Silence: The Psychology of the Portrait

Portraiture, in Sasai’s hands, is not a practice of likeness but of excavation. The human face becomes a surface through which internal states are rendered visible—not through symmetry or realism, but through disruption and weight. He frequently uses his own face as subject, not out of ego, but because it offers a site of unmediated access. This approach allows him to investigate emotional thresholds with rawness and continuity. His portraits often carry distorted features, sculptural volumes, and eyes that appear both searing and weary. These choices do not serve style; they serve truth. The distortions represent not an external mask, but the intensity of inner pressures—tension, fragility, fatigue, and occasionally, piercing moments of lucidity.

This commitment to interiority gives his paintings an emotional density that invites—and sometimes demands—introspection. The eyes, often the first and final points of engagement in his portraits, are treated with near-sacred focus. Sasai builds his compositions around them, working outward as though carving from a block rather than painting on a flat plane. Each mark is a negotiation between vulnerability and concealment. He has referred to this process as “chiseling the face,” a phrase that encapsulates his affinity for sculpture as a metaphor. Indeed, his portraits carry the gravity of something carved from time—bearing not only the features of the sitter but also the accumulated residue of looking, remembering, and confronting.

Texture and color play vital roles in this process, heightening the psychological charge of each canvas. Sasai gravitates toward earthy pigments—raw umbers, deep reds, ochres—that root the work in the corporeal. But these are often disrupted by flashes of jarring hues—acidic yellows, sharp violets—that puncture the quietude and destabilize the viewer’s expectations. These color choices are not ornamental; they act like emotional fissures, revealing layers beneath the surface. His handling of paint shifts from violent to tender, thick impasto giving way to translucent washes. This variability mirrors the flux of inner experience—the oscillation between calm and disquiet that defines his relationship with the act of painting.

Kouta Sasai: Between Tradition and the Contemporary Unknown

Navigating between his grounding in traditional Japanese environments and his international engagements, Sasai brings a quietly radical voice to the contemporary art conversation. His work resists easy categorization, inhabiting a space where cultural inheritance and modern introspection are not in opposition, but in dialogue. Living in wooden houses, working amidst the stillness of old towns, and exploring existential questions that transcend time, Sasai offers a unique fusion of setting and inquiry. His artistic practice is deeply personal yet resonates widely, precisely because it refuses to cater to external trends. Instead, it offers a form of visual contemplation—a still space in which viewers might recognize echoes of their own unspoken thoughts.

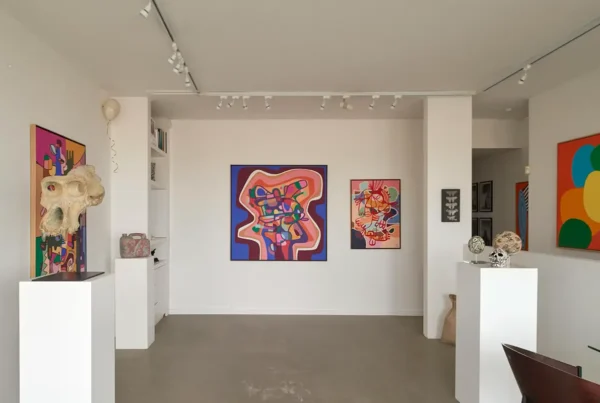

His exhibitions across the globe—from the United Kingdom to France and the United States—have demonstrated how his work transcends geographic boundaries. Viewers abroad often respond with directness to the psychological depth of his imagery, engaging with the discomfort and intensity rather than recoiling from it. In contrast, Japanese audiences tend to absorb his work through quiet observation, lingering in silence rather than reacting outwardly. Sasai finds meaning in both responses, valuing the invitation to pause and reflect above all else. At the Ruth Borchard Self Portrait Prize in the UK, his emotionally charged portraits were received with particular attentiveness, reinforcing his belief that painting can cross cultures without translation, provided it is sincere.

Ultimately, Sasai sees his task as one of listening—an effort to remain receptive to the past, attentive to the present, and open to the unknown. The studio becomes a threshold, not just between artist and canvas, but between presence and absence, form and dissolution. His paintings are born from this suspended space, where identity flickers and memory shifts, and where beauty lies not in resolution but in persistence. To be an artist today, in Sasai’s view, is to approach each work not as an answer but as a question left intentionally incomplete. Through this open-ended process, he creates spaces where both he and his viewers can encounter something quietly essential—even if only for a moment.