“I had found the solution to visualize my themes of climate change, sustainability and nature conservation.”

A Quiet Evolution from Journalism to Environmental Art

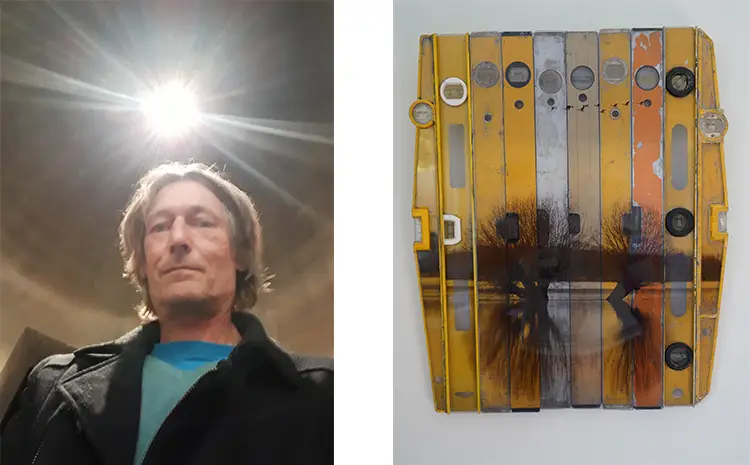

Rob Chevallier’s journey into the visual arts defies conventional timelines and expectations. Choosing to fully embrace his identity as an artist in midlife, his path was shaped by a complex interplay of professional choices, lingering doubts, and deeply rooted intellectual curiosities. Early advice steered him away from the uncertain terrain of an artistic career, prompting him instead to explore more stable roles—first as a librarian, then as a journalist. Yet even these vocations were anchored in creativity and a profound engagement with society. His diverse interests found a natural outlet in a graphic design course he pursued at 35, a pivotal experience where he discovered that photography and typography were his strongest tools for expression. This late-blooming clarity seeded a visual language that would evolve over decades, blending conceptual rigor with visual subtlety.

Chevallier’s first serious foray into photography occurred between 1992 and 1996, during his design studies. Though photography immediately captivated him, professional responsibilities initially hindered his ability to develop a cohesive artistic practice. It wasn’t until 2005 that he began exhibiting his work publicly, carefully curating selections that reflected his emerging interest in landscapes and industrial settings. This marked a turning point in his creative direction, coinciding with a growing awareness of climate change. However, he soon felt that traditional photography lacked the power to fully express the urgency and complexity of environmental degradation. In response, he moved beyond static documentation and began probing more abstract visual frameworks to explore ecological themes.

The decisive shift came in 2010, a year that marked both personal and artistic transformation. Choosing to leave his professional career a decade before retirement, Chevallier committed himself entirely to art. No longer satisfied with being a photographer presenting oversized prints or linear documentary series, he sought a new visual form capable of expressing nuanced ecological critiques. His commitment was not only to artistic innovation but also to engaging with humanity’s most critical challenge: the climate crisis. This inner drive set the foundation for the hybrid works that would follow—pieces that blur the lines between photography, sculpture, and social commentary.

Rob Chevallier: From Found Objects to Conceptual Installations

Chevallier’s artistic identity crystallized through his experimentation with photography, writing, and painting, but it was the serendipitous discovery of everyday objects at flea markets that unlocked a transformative new direction. These utilitarian artifacts, marked by visible signs of wear, became the foundation for a distinctive fusion of image and form. By pairing photographs with objects that bore the traces of past human use, he began crafting photo-objects and installations that speak to both memory and contemporary urgency. Initially, the objects functioned as simple backdrops or carriers for photographs. Over time, however, he cultivated a more intricate interplay between object and image—each component informing and amplifying the other.

This evolution reached a breakthrough moment when he encountered two old wooden spirit levels. What began as puzzlement over how to use one object became clarity when a second, similar piece emerged. The realization that he could construct a narrative across a series of objects, unified by a single photographic idea, sparked a creative revelation. These works began to tackle weighty themes—climate instability, sustainable practices, and ecological vulnerability—through carefully composed juxtapositions. In this way, Chevallier found a vehicle for making abstract environmental concerns palpable, tactile, and emotionally resonant. His installations aren’t merely visual experiences; they are meditations on imbalance, nostalgia, and human responsibility.

Integral to his process is the physical act of searching. Chevallier frequents flea markets and thrift shops weekly, not only for inspiration but as an essential ritual in his creative method. Sometimes the object itself catalyzes the idea for an artwork; at other times, a pre-existing concept drives the hunt for the right component. Regardless of approach, each piece must bear signs of past human activity, evoking a connection to history and collective memory. These worn surfaces serve as silent witnesses to both personal and societal evolution, which Chevallier contrasts with photographic imagery that captures present-day crises. In doing so, he offers a poignant reflection on a world increasingly out of sync—a world that, in his view, demands urgent artistic and ethical intervention.

The Visual Vocabulary of Influence and Memory

The roots of Chevallier’s creativity stretch back to his childhood fascination with a single encyclopedia—compact in size but expansive in scope. This formative book, filled with reproductions of iconic artworks, was a constant companion. Within its pages, he encountered the surreal dreamscapes of Dali and Tanguy, the kinetic sculptures of Tinguely, and the impressionistic visions of Monet and Turner. Magritte’s paradoxes, Van Gogh’s emotive brushstrokes, Seurat’s pointillism, and Warhol’s cultural critiques also left a lasting impression. This early exposure formed an internal gallery that still guides his sensibility. Rather than overtly mimicking these artists, Chevallier draws on their conceptual depth and visual diversity to inform his own hybrid creations.

His photographic eye was shaped later, and in a different context, by the precision and structure found in the work of Bernd and Hilla Becher. Their typological studies of industrial architecture provided a model for visual clarity and thematic rigor. This influence, combined with the panoramic compositional approach of Andreas Gursky, helped Chevallier refine his approach to image-making. While he ultimately departed from traditional photography, these visual methodologies continue to echo in his installations, particularly in their disciplined composition and balanced spatial logic. The influence is not literal but embedded in the underlying structure and tone of his work.

Rather than referencing canonical artists as distant idols, Chevallier integrates their lessons into a personal aesthetic rooted in activism, introspection, and transformation. The diversity of his influences mirrors the complexity of the issues he addresses—from environmental collapse to the erosion of cultural memory. His art does not seek to emulate but to dialogue with these artistic legacies, adapting their strategies to address contemporary concerns. By fusing the visual sensibilities of multiple traditions with his own ethical imperatives, Chevallier offers work that is both grounded in art history and unmistakably his own.

Rob Chevallier: A Tree Turned Warning, A Mirror Turned Hope

Among Chevallier’s many works, The Nitrogen Tree stands out as a synthesis of his thematic concerns and artistic techniques. The piece confronts the looming ecological threats posed by nitrogen and CO₂ emissions, symbolized by a solitary tree that becomes a figure of both fragility and resilience. The tree embodies nature’s quiet endurance in the face of mounting storms, floods, and human-induced damage. Yet it is not a passive subject; this tree demands attention. It represents a warning and a plea—reminding viewers that the strength of the natural world is not infinite and must be protected with urgency.

The installation takes on added meaning through its material composition. Hanging from the branches (exhaust pipes) are used metal bowls, repurposed as leaves. Their presence emphasizes sustainability and the importance of rethinking consumption. Each reused object carries its own narrative of utility and decay, reinforcing the message that a sustainable future depends on how we handle the remnants of the past. More dramatically, the piece features 100 photographs of trees suspended upside-down. This inversion signals a deep disorientation in our relationship with nature. It’s a visual alarm: the natural order has been upended. But Chevallier doesn’t leave his audience without a way forward.

Surrounding the artwork are car mirrors—deliberate choices meant to confront the viewer with their own reflection. In seeing themselves mirrored within the work, observers are urged to engage in self-examination. These reflective surfaces turn the piece into an introspective experience: if nature appears distorted, perhaps it is because we are looking at it from the wrong perspective. Chevallier suggests that restoration is possible—but only if we are willing to confront uncomfortable truths and change our behavior. The Nitrogen Tree is not just a piece of art; it is a call to awareness, an invitation to reevaluate priorities, and a subtle but insistent demand for environmental accountability.