“The flower is destroyed in order for its image to endure, so each cast becomes a kind of death shroud.”

Collecting the Ephemeral

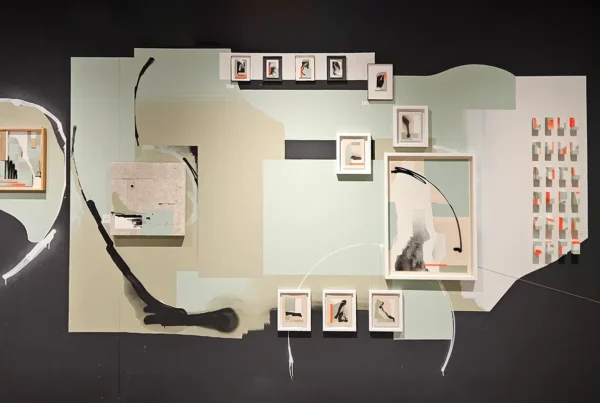

Maggie Shafran‘s practice emerges from a deep engagement with the transient and the tender. A multidisciplinary artist working across painting, plaster casting, photography, drawing, and sewing, she navigates the porous boundaries between presence and absence, between what is preserved and what inevitably fades. Her work is grounded in a careful attention to everyday encounters and the instinct to archive fleeting moments before they vanish. Shafran’s approach is not fixed to any one medium; instead, she chooses her materials based on the emotional and conceptual resonance of the subject, allowing each form to unlock distinct possibilities of meaning. Her pieces echo a quiet urgency—an effort to hold onto beauty while acknowledging its impermanence.

Raised in a home marked by warmth and commotion, Shafran found solace early in artmaking. She recalls the comfort of retreating to a small desk tucked away from household chaos, where drawing became an anchor in a sea of unpredictability. That formative experience shaped not only her creative path but also her way of processing life. Art became more than a pastime; it became a method of making sense of things too overwhelming for language. After earning a Fine Art degree at Pitzer College, her practice took root in Los Angeles and Sun Valley before a pivotal move to London. Graduate studies at the Royal College of Art and Camberwell College of Arts expanded both her techniques and her conceptual frameworks. The move also attuned her more closely to the emotional charge of small, intimate details—those minor moments and objects that quietly tether us to time and memory.

The subjects that preoccupy Shafran—impermanence, grief, fragility—are reflected not just in the themes she explores but in the processes she adopts. Photography often initiates the work, not as an end in itself, but as an act of gathering. Through sketching, stitching, and casting, these collected images evolve into layered compositions, each iteration further abstracting the original encounter. Her practice unfolds like a meditation on memory: imperfect, fragmented, and always shifting. Yet through this fragmentation, a sense of continuity emerges—one that honors the complexities of longing and the human impulse to preserve what inevitably slips away.

Maggie Shafran: A Language of Loss and Intimacy

Shafran’s evolving visual language finds strength in paradox. Her works are consistently shaped by opposing forces—intimacy and rupture, beauty and deterioration, the physical and the spectral. These dualities serve not only as thematic anchors but also as structural principles, guiding her decisions in form and content. The materials she chooses become agents of translation. A dried flower, a weathered object, or a familiar photograph might be reimagined through graphite, pigment, thread, or plaster. This act of transformation is central to her vision: by shifting mediums, she allows herself to explore not just the object itself, but the emotional atmosphere it holds.

At the core of her recent projects lies a desire to honor absence by making it visible. Objects passed down from her mother’s family have become vessels of emotional resonance. A green sweater, an old pen, a silver tray—these artifacts are not passive remnants, but active participants in Shafran’s exploration of memory. In her ongoing “Inhabited Objects” series, she treats these heirlooms as portals through which the past continues to flicker into the present. By photographing their surfaces and working those images into paintings and compositions, she distorts clarity to reflect the incomplete and often ambiguous nature of remembrance. The process of cropping, enlarging, and reframing creates an interplay between familiarity and estrangement, inviting viewers to find their own reflections within these abstracted echoes.

Shafran’s style resists easy categorization. It adapts in service of the subject, shaped by a persistent need to find the most meaningful way to express a particular feeling or idea. Though diverse in execution, her bodies of work are threaded together by a shared undercurrent: the act of holding on. Whether through stitched fragments of Dutch floral still lifes or the delicate casting of a cosmos flower, her art arises from a compulsion to preserve what cannot last. The result is a collection of visual records that speak to the ephemeral nature of life while offering a quiet resistance against forgetting.

Histories Folded Into Form

In her three main bodies of work—Little Pieces of Death, Fragments, and Inhabited Objects—Shafran investigates how beauty, decay, and longing coexist. Little Pieces of Death, which began during the isolating period of the first Covid lockdown, stems from an overwhelming encounter with abundance. Living on a farm in the English countryside, she became fixated on the brief lifespans of the surrounding flowers. Their impermanence, heightened by the eerie stillness of global uncertainty, spurred a need to preserve. Moving beyond the camera, she began creating silicone molds of the blooms and casting them in plaster. These delicate sculptures, ghostlike in their whiteness, are marked by contradiction—they survive only through destruction. The original flower must perish for its likeness to remain.

These casts, porous and brittle, are then touched with watercolor ink, which bleeds slowly into their forms. The ink mimics blood or memory seeping into a body, reinforcing the tension between life and lifelessness. But the work does not end there. Shafran continues to photograph the sculptures, manipulate the images, and reassemble them into collages. Each transformation becomes a distancing from the source, an act of mourning, and a rebirth. The process mirrors how memory works: never stable, always mutating, yet clinging to something essential. These preserved fragments, though devoid of life, acquire a new kind of presence—an elegy in physical form.

In Fragments, Shafran turns to Dutch floral still lifes, particularly the opulent yet somber compositions of Jan van Huysum. His baroque arrangements teem with vitality while simultaneously hinting at decay: insects crawl, fruit begins to rot, and funerary motifs lurk beneath ornamental surfaces. Using high-resolution reproductions, she isolates details that often go unnoticed. She draws these with charcoal and graphite, stripping the lush paintings of color to underscore their quieter, more somber narratives. By sewing the panels together with threads that match the original hues, she references both anatomical repair and the artifice of the compositions themselves. The stitching becomes both structural and symbolic, reinforcing her recurring interest in reassembly, fragmentation, and the impossibility of true preservation.

Maggie Shafran: Encounters with Reflection

Shafran’s most recent investigations push deeper into the poetic possibilities of inherited objects, particularly through the project Inhabited Objects. Here, silver trays from her mother’s side of the family serve as reflective surfaces through which time collapses. The trays do not merely reflect their surroundings; they absorb them. In photographing the trays while wearing her mother’s green sweater, Shafran discovers a visual entanglement—the past merges with the present in quiet, ghostly overlays. These subtle distortions become the basis for a new body of oil paintings that stretch between hyper-realism and abstraction. The reflections are ambiguous, layered with both clarity and concealment, echoing how memory functions as both anchor and illusion.

This work is not about the objects alone but about the psychological distance they carry. Shafran manipulates the photographs to obscure, zoom in, or crop out key features, creating an estrangement that mirrors her own partial understanding of her family’s history. By presenting these distorted images as paintings, she transforms them again, layering meaning atop meaning. Some compositions are rendered in soft, loose gestures, allowing the paint to speak in its own language. Others adopt precision, sharpening the emotional resonance through tight focus and controlled technique. These contrasts reflect the nature of loss itself: at times blunt and raw, at other times diffuse and elusive.

The use of diptychs introduces an added complexity. By pairing images that may or may not directly relate, Shafran invites open interpretations. These arrangements disrupt linear storytelling and reflect the fragmented, nonlinear character of remembering. Her studio practice revolves around an active rhythm of observation, collection, and reinterpretation. Whether sketching new ideas, listening to audiobooks that influence her titles, or collaborating with fellow artists, she nurtures an environment where process is as vital as product. Upcoming works include a new piece framed by a friend who specializes in traditional wood carving, inspired by a shared viewing of Jan van Huysum’s paintings. Projects like this continue to anchor her work in community, memory, and tactile engagement with history.

Shafran’s art carries a quiet intensity—an unwavering commitment to investigating how meaning is stored, lost, and recovered. Through material exploration and emotional excavation, she constructs a delicate architecture of remembrance, inviting others to peer into their own reflections.