“Treat trash like jewels and jewels like trash.”

The Quiet Shadows of Origin

Growing up in a post-civil war Spain shaped by silence, conformity, and latent unrest, Jaime Roig de Diego found his first expressive tools not in an art studio but on hallway walls and military instruction manuals. Born just over a decade after the Spanish Civil War, he was raised in a setting steeped in restrained tension—a society visibly stitched together, yet unable to conceal its scars. His childhood, spent in a military residential zone surrounded by dry landscapes and ominous structures like skin-drying facilities for animal remains, offered little in terms of visual stimulation. Still, young Jaime turned the void into a canvas. A sickly child often kept indoors, he began drawing wherever he could: walls, floors, even a breakfast tray still bears the trace of one of his early “brides with a train.” These impromptu surfaces became his first sketchbooks, each scribble an attempt to process the bleak surroundings that shaped his inner world.

Despite the oppressive environment and minimal artistic encouragement, Roig de Diego’s imagination found fertile ground in the surreal. A pivotal moment came at age eleven when he discovered Salvador Dalí—a figure whose fantastical narratives and flamboyant imagery offered both escape and inspiration. Soon after, Andy Warhol entered his field of vision, expanding the spectrum of possibility with Pop’s commercial boldness and conceptual weight. But the road to art was not linear. While he longed to work in film, Roig de Diego ultimately pursued studies in Advertising and Communication, areas that would later inform his visually saturated yet critically nuanced style. His background in advertising would not just support his art but shape the framework through which he approached it: iconography, symbolism, and the power of condensed visual storytelling.

From the beginning, Roig de Diego perceived himself as an artist—not by choice, but by essence. Even his early declarations of wanting to be a dancer or a writer hinted at an instinctive pull toward forms of expression that demanded complete personal engagement. The artist didn’t wait for validation or a formal “start” to his career. It simply was. Over the years, he immersed himself in both theoretical and practical studies, attending the Fine Arts Circle of Palma and the Pilar and Joan Miró Foundation, among others. His participation in film, radio, and theater projects came naturally, further underscoring his belief that the artistic identity is not tied to medium or moment, but to the constant act of observing, creating, and translating lived experience.

Jaime Roig de Diego: Icons, Irony, and the Pulse of Critique

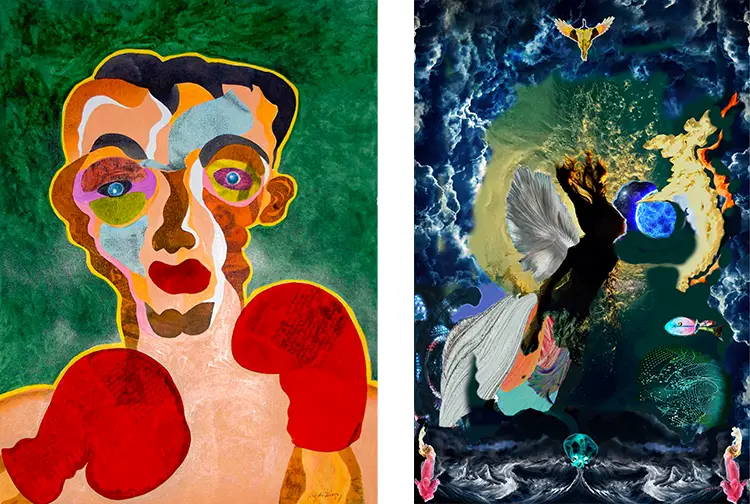

At first glance, Jaime Roig de Diego’s work fits within the parameters of Pop Art, but the surface only tells part of the story. He has long resisted singular classification, instead offering a hybrid approach he defines as Spanish Pop Surrealism—a figurative, often biting form that simultaneously critiques and celebrates the culture from which it springs. The Spanish influence is unmistakable, not just in palette or symbol, but in the way his work confronts its audience with familiar figures rendered unfamiliar. In series like “Chicas Convulsas” and “Argumentos Faciales,” Roig de Diego turned to the human form as a vessel for sociopolitical commentary, critiquing everything from beauty standards to pharmaceutical escapism. These weren’t passive portraits but reflective surfaces for a society more concerned with Botox than authenticity.

His ability to thread satire through glossy, Pop-styled images allowed his work to reach a wide audience while maintaining its critical edge. The tension between fascination and guilt runs deep in these pieces, particularly as they evolve. The updated “Chicas Convulsas,” for example, express environmental anxiety, reacting not just to shifting aesthetics but to shifting global priorities. One artwork description offers a sharp juxtaposition: the turkey—once seen as a diet-friendly meal—becomes a grotesque symbol of consumer ignorance, identified not for its ecological relevance but its nutritional convenience. This dark humor, often laced with linguistic wit and visual irony, is emblematic of Roig de Diego’s artistic voice, where every brushstroke or digital layer holds a pointed subtext.

Environmental themes culminated in his 2022 solo exhibition, “ABISME / ABYSS / ABYSSUS,” held at Fundació Sa Nostra in Palma de Mallorca. This project marked a notable shift, both in scale and gravity. Taking cues from Homer’s mythic descriptions of the Mediterranean as wine-colored or blood-like, Roig de Diego painted a damning portrait of human negligence toward the seas and oceans. While still embedded in his Pop sensibilities, this body of work abandoned playfulness in favor of confrontation. It served as a culmination of his evolving perspective: no longer content to merely observe or satirize, the artist now sounded an alarm, calling viewers to acknowledge the devastating cost of cultural detachment from nature. The exhibition reaffirmed Roig de Diego’s ability to adapt his voice without diluting its potency—delivering urgency with poetic precision.

Medium as Message, and the Alchemy of Trash

Roig de Diego’s relationship with materials has shifted as dramatically as his subject matter, with each transition serving a conceptual purpose. His early Pop works employed acrylics and transfers to emulate the sleek, illustrated finish of commercial print media. But it was his embrace of digital tools—initially for advertising—that opened up new artistic frontiers. Using those same programs to deconstruct celebrity culture, he launched the “CELEBRITIES” series, where politicians, pop stars, and public figures were placed into absurd, sometimes uncomfortable situations. Long before AI-generated art became widespread, Roig de Diego was manually composing digital pastiches that blurred the lines between satire and critique. The project gained traction and acclaim, but its commercial success eventually felt restrictive. Seeking new terrain, he left the digital screen behind and turned to tactile materials—specifically, waste.

The decision to use discarded objects was both philosophical and practical. Disturbed by the demonization of plastic and widespread disinformation surrounding sustainability, he coined the phrase, “Treat trash like jewels and jewels like trash.” This motto encapsulated not only his aesthetic pivot but also his ideological stance. The shift was as much about materials as it was about meaning. What society discards, Roig de Diego reclaims—not just as a protest, but as a radical act of reevaluation. Childhood memories of collecting fake jewelry, driven by an inexplicable attraction to shiny objects, suddenly found adult validation in these new compositions. The artist began embedding social critique into physical form, marrying kitsch with commentary in works that forced viewers to reconsider the perceived value of objects and symbols.

This new material phase also aligns with Roig de Diego’s evolving interest in accessible art. His upcoming project, which includes small-scale sculptures, is aimed at young collectors. Rather than create works meant to intimidate or overwhelm, he’s designing art that fits within contemporary living spaces—physically, economically, and conceptually. The goal is to democratize ownership without diluting vision, engaging a generation that may not have gallery walls but does have cultural awareness. Roig de Diego sees the artist not as an elite provocateur, but as a cultural participant—someone who offers pieces that resonate, challenge, and ultimately, connect. These new sculptures will continue his tradition of embedding meaning in material, extending his unique dialogue with form and function to new, more intimate dimensions.

Jaime Roig de Diego: Language, Legacy, and the Power of the Apron

In Roig de Diego’s contribution to the “DAVANTALS” series, a simple domestic garment becomes a conduit for social commentary, historical critique, and linguistic excavation. The apron—often seen as benign or functional—unfurls into a symbol of layered oppression when examined through his lens. Drawing from feminist literature, popular culture, and historical narratives, he dissects how the apron has long served as both a literal and metaphorical shackle, especially for women relegated to domestic roles. Unlike the rugged aprons worn by male tradesmen—discarded the moment work ends—the female apron clings with persistence, even appearing at weddings and public celebrations. His artwork confronts this troubling endurance, transforming the apron into a vertical surface filled with graffiti-like proverbs. Each phrase is a cultural fossil, embedded in public consciousness and passed down through generations.

Roig de Diego doesn’t simply present the apron as an artifact; he constructs it as a narrative wall. The work begins at its base with linguistic roots—common sayings and adages in Spanish, Catalan, and English that encode sexist ideologies. These are not quoted to provoke but to reveal, functioning as a mirror to the language that subtly perpetuates inequality. As the composition ascends, the graffiti evolves into ornamental patches—visual metaphors for how such ideas cling to tradition without truly belonging. The piece culminates in a transformation: what begins as a functional garment morphs into an elegant bodice, crowned with guipure lace, signifying a potential for redefinition. In this act of visual reassembly, the artist reclaims the apron not just for critique but for possibility.

Responses to this work have been as complex as the piece itself—ranging from visceral rejection to poignant affirmation. Some viewers saw only the offensive language and missed the critique embedded in its recontextualization. Others recognized themselves, or their culture, in the uncomfortable truths stitched into the fabric. For Roig de Diego, these reactions validate the purpose of conceptual art: to unsettle, to expose, to invite dialogue. He approaches such pieces not from a place of ego, but from a sense of social responsibility shaped by his background in advertising and journalism. For him, the artist’s duty is not to please, but to reflect—with clarity, purpose, and an unwavering commitment to the truth embedded in everyday symbols.