The Weight Beneath Stillness

In the northern Romanian town of Baia Mare, Adrian Ghenie first encountered the subtle psychological tensions that would later define his art. Born in 1977 into a family with no artistic background—his father worked as a dentist—Ghenie grew up surrounded by a quiet unease, a sense that the visible world was merely the surface of something far more complex. That childhood intuition stayed with him. Even in his earliest thoughts about painting, he sensed that images could convey contradiction, carry obsession, and serve as vessels for elusive emotional realities. Rather than simply represent the world, Ghenie’s future canvases would aim to unsettle it, probing into the fractured spaces where memory, identity, and history collide.

His education began at the Arts and Crafts School in Baia Mare, where he became fluent in the technical language of image-making. This phase introduced him to the physical labor of painting—how to manage materials, compose a scene, and build a visual structure. However, it was during his later studies at the University of Art and Design in Cluj-Napoca, from which he graduated in 2001, that Ghenie began to engage with the deeper philosophical questions of art. Here, technique gave way to concept, and his interests expanded into the psychological and political tensions that painting could capture. He no longer saw the canvas as a space for rendering reality, but as a site of confrontation—where historical brutality and aesthetic seduction could exist in mutual disturbance.

Following a period in Vienna, Ghenie returned to Romania in 2005 with a sharpened awareness of the disconnect between Eastern European artists and the broader global conversation. Alongside Mihai Pop, he co-founded Galeria Plan B in Cluj. More than a traditional exhibition space, it was conceived as a platform for discourse and production—an intervention aimed at breaking the geographic and ideological isolation many Romanian artists faced. The expansion of Plan B to Berlin in 2008 further amplified their international presence, signaling a shift not only in Ghenie’s career but in the global perception of contemporary Eastern European art.

Adrian Ghenie: Subconscious Architectures

In his early solo exhibitions, Ghenie turned his focus inward—not in a purely autobiographical sense, but in search of interiority itself. Works such as Basement Feelings and Memories, both from 2007, exemplified this phase. The scenes depicted were not overtly dramatic: bare rooms, generic offices, empty corridors. Yet these environments pulsed with psychological charge. Ghenie transformed the mundane into arenas of unease, places where forgotten traumas and suppressed memories seemed to hover just beyond recognition. These compositions were not literal recreations but dreamlike reconstructions, imbued with the uncanny sense that something irreversible had already occurred.

Rather than approach the subconscious through surrealism’s fantastical aesthetics, Ghenie opted for a subtler vocabulary—blending figuration with spatial ambiguity, color with corrosion. His staging of banal interiors became a form of psychoanalysis rendered in oil. The viewer was left to wander these painted spaces like a memory palace, sensing the echoes of lives and losses without being given explicit narratives. Through these works, Ghenie proposed that history is not only written in books and monuments but is embedded in spaces, bodies, and gestures, often buried in the margins of the ordinary.

History would continue to shape Ghenie’s output, though never in the form of clean chronology. His treatment of historical figures—whether dictators, philosophers, or cultural icons—has always resisted simplification. Faces are smudged, limbs are blurred, identities appear in flux. His canvases do not seek to represent individuals so much as interrogate what they symbolize. These characters become stand-ins for collective anxiety, for the murky terrain where ideology, trauma, and power intersect. Ghenie’s approach is less documentary than forensic—using distortion as a way to question what images of the past reveal, and more crucially, what they conceal.

Painting Collapse, Comedy, and Corrosion

In the series known as the Pie Fight paintings, Ghenie introduced a jarring mix of absurdity and darkness. Borrowing imagery from slapstick comedy—particularly routines made famous by the Three Stooges—he covered his figures in cream pies and chaos. But the humor here was laced with menace. These works were not celebrations of levity; they were meditations on failure, shame, and the grotesque theatre of power. The pies became masks of humiliation, the figures grotesquely caught between comedy and collapse. In these frames, Ghenie blurred the boundary between the clown and the tyrant, inviting viewers to reflect on how farcical performances often hide more sinister undertones.

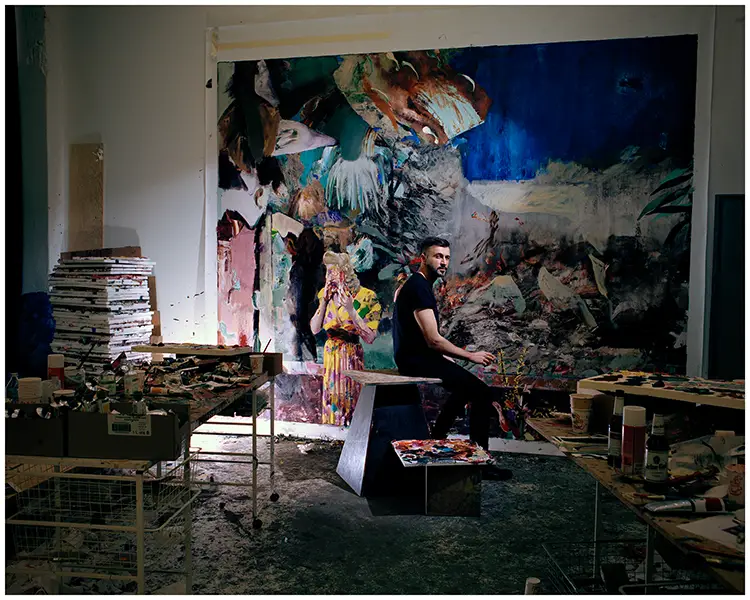

His process reinforces this thematic tension. Traditional brushwork is largely absent from Ghenie’s canvases. Instead, he employs palette knives, scrapers, erasers—tools more often associated with destruction than creation. This aggressive surface treatment reflects his conceptual belief that painting must undergo a kind of ordeal to become meaningful. Each image bears the marks of its own undoing, with layers scraped away, reconstructed, and buried again. What emerges is a visual archaeology, a surface that retains the memory of every intervention. This ethos has migrated into his drawing practice as well, particularly in his recent experiments with charcoal. By erasing and redrawing, Ghenie allows the image to reveal itself slowly, as if coaxed from darkness.

A pivotal moment came in 2015 with Darwin’s Room, his project for the Romanian Pavilion at the Venice Biennale. More than an exhibition, it was an immersive installation—an environment that enveloped the viewer in chiaroscuro tones and psychological density. While the title invoked Charles Darwin, the focus was not on the scientist himself but on the broader idea of evolution—cultural, ethical, emotional. Referencing Rembrandt’s The Philosopher in Meditation, the space suggested contemplation but offered no conclusions. Absence played a central role. Human presence was implied but never shown, underscoring Ghenie’s belief that painting can evoke presence through voids, through the shadows of what has vanished or been erased.

Adrian Ghenie: Chaos as Critique

With Dada Room, another significant installation, Ghenie deepened his exploration of irrationality and disorder as a form of resistance. Inspired by the radical legacy of the First International Dada Fair, he constructed an environment thick with debris—textures, clashing forms, fractured signs. It was less a homage than an invocation. The installation functioned as a living collage, assembled from pieces of his own painterly language. The result was a chaotic symphony of rejection, aimed squarely at the structures—political, academic, aesthetic—that promote illusionary coherence. In this dimly lit setting, logic gave way to instinct, and sense-making was replaced by sensation. It was a call to re-engage with the irrational as a legitimate mode of expression.

Throughout his career, Ghenie has acknowledged a lineage of influence that includes Otto Dix, Willem de Kooning, and Vincent van Gogh. What unites these figures, in his view, is their willingness to let volatility shape their art. Dix confronted the moral wreckage of war with clinical precision. De Kooning shattered form with gestural abandon. Van Gogh transformed pigment into pure feeling. Rather than imitate them, Ghenie positions his work as a continuation of their inquiries—pushing the tensions between clarity and chaos, figuration and abstraction. His canvases are not stable images but volatile fields, where past and present jostle for space and meaning.

This tension reached a broader audience with The Sunflowers of 1937, a painting that achieved a record-breaking sale at Sotheby’s in 2016. The work is both a nod to Van Gogh and a reflection on the political darkness of 1937—a year marked by totalitarianism and looming catastrophe. In merging these two reference points, Ghenie created a piece that felt uncannily resonant. But for the artist, success lies not in auction records but in the painting’s capacity to keep posing questions long after it leaves the studio. He remains indifferent to market validation, focusing instead on whether a work unsettles, provokes, or reveals something previously obscured.

Today, Ghenie’s paintings hang in leading institutions like the Centre Pompidou and the Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles. Yet his objectives remain consistent. He hopes that viewers leave his work with more uncertainty than clarity—disoriented, perhaps, but more attuned to the complexities they carry. In an era driven by speed and spectacle, he sees painting as a necessary interruption, a medium that demands slowness, depth, and discomfort. For Ghenie, painting is not about capturing what is visible. It’s about recovering what has been buried.