“Stop composing. Whenever I get stuck or frustrated, it’s a mantra; and I get back to work.”

Beneath the Surface: The West Texas Echoes That Shape a Practice

Emerging from the rugged, sun-drenched landscapes of Odessa, Texas, Shayne Brantley carries the imprint of a place defined by contradiction. The city, known for its arid heat, oil-fueled industry, and cowboy culture, has deeply influenced his visual language. Odessa isn’t just a backdrop but a foundation, where the raw physicality of the land meets the enduring myths of the American West. In Brantley’s memory, the sky was always split between the industrial silhouettes of pumpjacks and the vast quiet of the high plains. That kind of contrast continues to influence his creative instincts. The Odessa Meteor Crater, a massive prehistoric impact site, also looms large in his consciousness—a reminder of sudden, transformative force. Growing up where meteorites once fell and roughnecks now drill, Brantley developed an eye for unexpected collisions, a sensibility that later became central to his artistic ethos.

Long before abstraction or material experimentation entered his vocabulary, Brantley was absorbing the visual and emotional cues of his hometown. High school football, for instance, wasn’t just a weekend ritual—it was a cultural imperative that knit the community together. Odessa Permian High School, his alma mater, later gained national recognition as the basis for “Friday Night Lights.” That communal intensity, where identity was forged in the bleachers and on the field, left a mark. Brantley’s background—rooted in family life, public service through his father’s medical practice, and the shared rituals of a small town—imbued him with an appreciation for the unspoken narratives that underlie surface appearances. Even in his early days working at the Greyhound bus station, he witnessed the cyclical churn of bodies and machinery tied to the oil economy. These scenes, seemingly mundane, laid the groundwork for his ongoing interest in layered meaning.

Brantley’s artistic approach can be traced back to the amalgam of those early contradictions: the brutality and beauty of nature, the mechanical and the personal, the intimate and the epic. Odessa’s starkness trained him to see how absence could be as powerful as presence. His work thrives in tension—between color fields and rendered forms, between figuration and texture—echoing the environment that first taught him how to look. While his materials are traditional—paint, pencil, metal, wood—the experiences that inform their use are anything but conventional. It is in this setting that Brantley’s eye for juxtaposition was first sharpened, not through art history textbooks, but through lived paradox.

Shayne Brantley: The Art of Letting Go and Scraping Back

In the early 1980s, Brantley’s journey into artmaking took a decisive turn when he enrolled at Austin College in Sherman, Texas. Initially, he approached his work with a conceptual looseness, attempting to avoid fixed ideas or expectations. However, such neutrality proved short-lived. Formal concerns quickly began to dominate until an unexpected challenge from his instructor, Joe Havel, altered his trajectory. Havel’s simple directive—“Stop composing”—was more than advice; it was an awakening. That phrase became Brantley’s compass, enabling him to shift from intentionality to instinct. The experience catalyzed a practice that encourages accident, resists polish, and rewards exploration. From that moment, he began to treat drawing and painting not as destinations but as acts of discovery, shaped as much by erasure and failure as by precision and control.

Brantley’s process-oriented philosophy fully matured during his time at the University of Minnesota, where he pursued an MFA and later attended the Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture in Maine. Skowhegan reinforced his confidence and encouraged him to scale up both conceptually and physically. After completing his formal education, he relocated to New York City, a period of his life marked by both artistic output and practical survival—painting and drawing during the day, driving a cab to make ends meet. These dual roles, one creative and one pragmatic, mirror the friction that continues to fuel his work. He regards his output as direct and sincere, not burdened with irony or satire. Instead, his pieces seek openness, embodying a subtle existential curiosity. They are born from the belief that meaning exists without the need for justification or narrative.

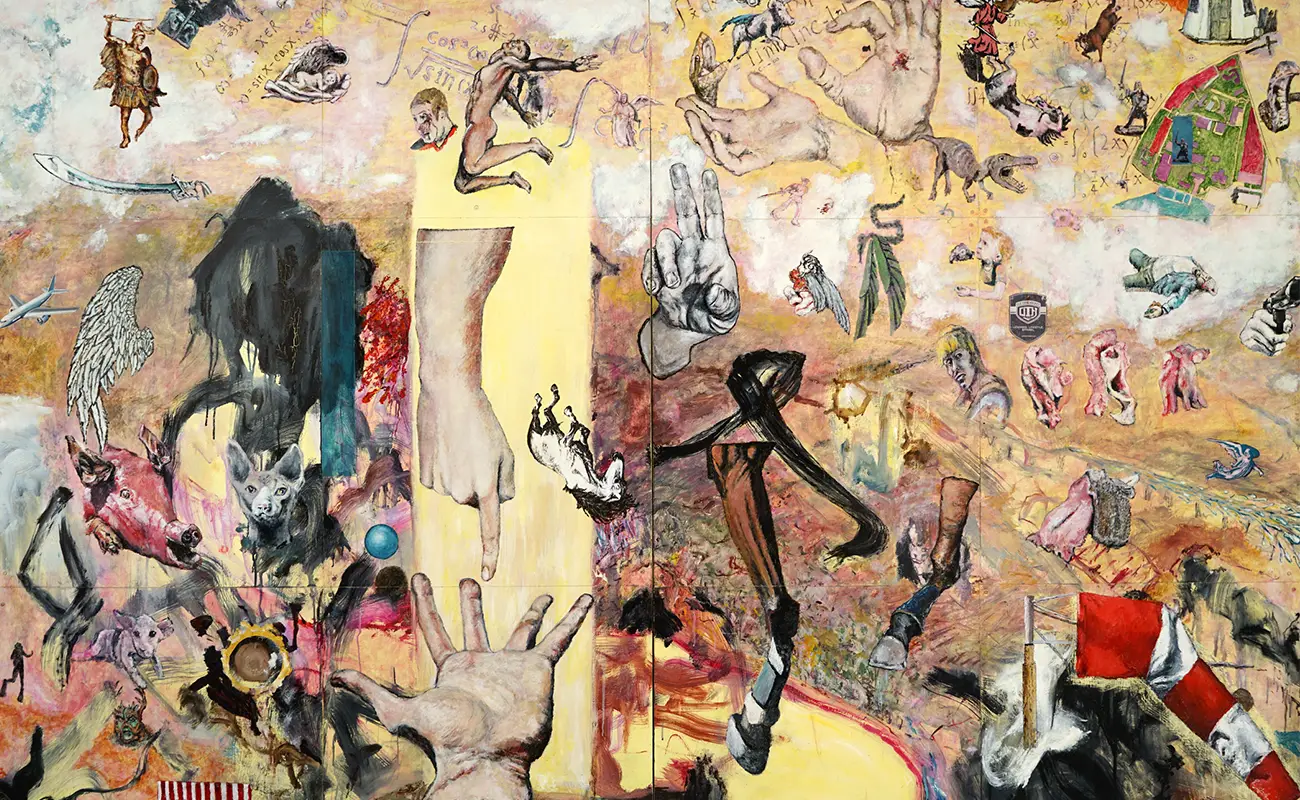

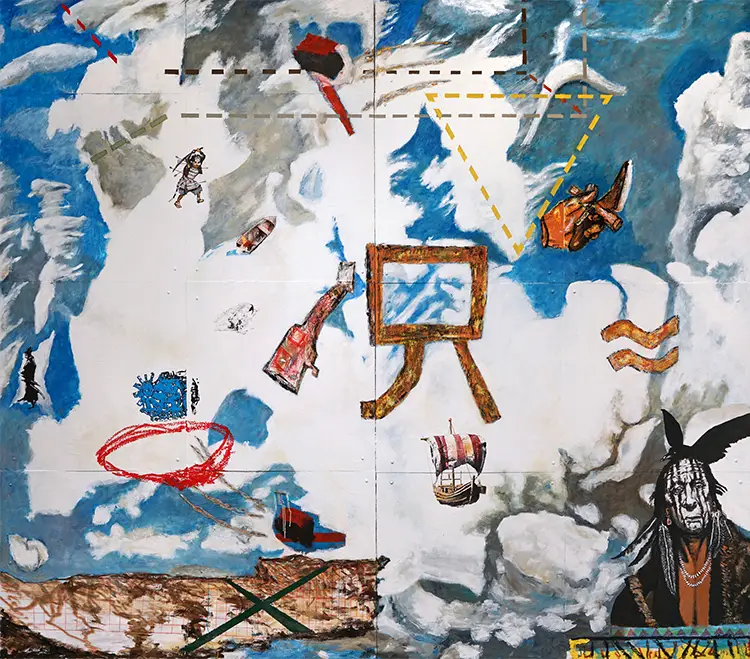

At the core of Brantley’s style lies a fascination with process. His technique involves applying layers of media—paint, pencil, ink—onto various surfaces such as metal, wood, paper, or canvas, only to aggressively scrape, gouge, or remove those layers. This act of construction and deconstruction is more than aesthetic; it is philosophical. It suggests that clarity often emerges from disruption. Within these physical strata, the artist finds what he calls “pleasingly unanticipated results.” Some images survive this excavation; others are lost, becoming ghosts beneath the surface. His large-scale works like “Popcorn as Asteroid” and “Chick,” both housed in private Houston collections, exemplify this dialogue between intention and accident. In contrast, smaller pieces like “Teacup,” rendered on metal, demonstrate that intimacy and impact are not mutually exclusive.

Chaos, Color, and the Courage to Begin Again

Brantley’s practice is sustained by an enduring curiosity about material and meaning, often triggered by the unexpected. He doesn’t rely solely on traditional sources of inspiration like canonical painters or textbook movements. Instead, it is often the glint of a particular color on a weathered house or the peculiar way light strikes an object that catalyzes new work. He keeps his creative channels open to fleeting impressions, allowing even the most trivial details to inform his approach. His process reflects this openness. He regularly finds himself starting anew, not out of frustration but as a core strategy. Using a wire brush attached to a drill, he physically wipes away layers of paint, exposing residual marks and textures. These acts of erasure become creative openings rather than failures, allowing the work to reform in unexpected ways.

The quote that governs much of Brantley’s working life comes from Samuel Beckett: “Ever tried? Ever failed? No matter. Try again. Fail again. Fail better.” These words reflect his belief that failure is not a sign of defeat but a vital step in the progression of an artwork. For Brantley, each piece contains the risk of collapse and the possibility of revelation. That risk, and the freedom it offers, is essential to his artistic identity. Unlike many artists who arrive at a clear style or thematic throughline, Brantley thrives on fluidity. Themes may recur, but they are never rigid. He prefers to let ideas emerge organically, often in juxtaposition or contradiction. The pieces serve less as declarative statements and more as open invitations to interpretation, with each layer offering a different visual or emotional entry point.

One of the most defining aspects of Brantley’s practice is his detachment from traditional notions of authorship or meaning. He refrains from assigning definitive value or explanation to individual works. To him, the significance of a painting or drawing lies not in its origin but in its ability to mirror or engage with the viewer’s perception. The medium itself becomes the message, not in a theoretical sense, but as an embodied truth. Whether executed on a vast canvas or a sheet of paper, his works are about presence—the presence of color, material, gesture, and time. This insistence on process over product, and the artist’s willingness to be surprised by his own work, gives Brantley’s art its distinctive depth and elasticity.

Shayne Brantley: Where Art Finds the Artist

For Brantley, studio life isn’t segmented into projects or plans—it’s a continuous rhythm of engagement. Each day presents the possibility of a new beginning, and that open-endedness is vital to how he functions creatively. He doesn’t chart out future bodies of work or chase thematic consistency. Instead, he waits for the work to emerge in its own time, trusting that it will arrive when it’s ready, or more accurately, when he is. This organic approach keeps the act of making alive and fluid. There is no production schedule, no looming conceptual framework. Art, for Brantley, is a daily commitment, a physical and mental practice that maintains its vitality through repetition and reinvention.

The unpredictable nature of his process doesn’t mean a lack of discipline; rather, it requires a sustained attentiveness to the materials and their demands. He approaches each surface with a sense of curiosity, treating them as sites of potential rather than predefined outcomes. Whether he’s working on paper, wood, canvas, or metal, the tools he chooses—often simple and direct—serve as extensions of his thought process. Paint is applied, scratched, pulled, and re-applied, each gesture a response to what came before. Sometimes a piece emerges quickly; other times it undergoes prolonged cycles of revision. This elasticity is not a hindrance but a strength, allowing for greater responsiveness to the unknown, which Brantley embraces rather than resists.

What the future holds in terms of specific works or directions remains undefined, and that lack of definition is, for Brantley, exactly where the excitement lies. He does not set out to resolve questions or assert finalities. Instead, he allows his practice to unfold as a lifelong conversation, one that is sustained not by certainty but by engagement. Whatever form his next project takes, it will likely emerge through the same intuitive dance between building and scraping, presence and absence, accident and intention. In his own words, the work will find him when he finds it—and that patient reciprocity continues to be the driving force behind his evolving practice.