“If we can control the darkness inside of us, the world would be a lot better place.”

A Stranger in the Familiar

In the quiet outskirts of Grove City, Pennsylvania, Phillip Everett Caldwell crafts art that feels anything but quiet. At 39 years old, Caldwell occupies a space that resists easy definition. His work shatters conventions, stepping into unsettling territory that confronts the viewer with grotesque beauty and visceral introspection. Rather than chasing approval or aesthetic harmony, he draws power from alienation itself—embracing the feeling of being an outsider not as a wound but as a creative vantage point. That dissonance with societal norms fuels a body of work that is bold, confrontational, and psychologically charged.

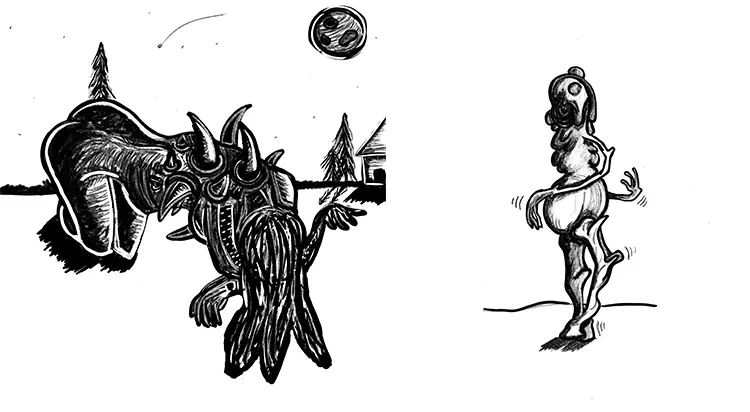

Caldwell’s art is intimately tied to his sense of identity, sharpened by years of being “the odd man out.” He channels that outsider experience into a visual language that thrives on darkness—both thematically and tonally. Through surreal and often monstrous figures, he gives form to emotions and memories that are typically left unspoken. The result is art that does not seek to soothe or reassure, but rather to compel and disturb, allowing viewers to wrestle with their own interpretations. This candor in confronting the darker aspects of human nature has become a core strength of his practice.

Rather than turning away from the shadows of life, Caldwell finds clarity by facing them head-on. He views self-awareness not merely as a personal trait but as a form of power—one that allows him to create without inhibition. This transparency permeates his process. He doesn’t just depict monsters or disfigurements; he explores the feeling of otherness itself, constructing forms that sit uncomfortably between categories. These ambiguous figures become extensions of the artist’s inner world: hybrids of thought, trauma, memory, and speculation that challenge the boundaries of form and meaning.

Phillip Everett Caldwell: Ink, Imagination, and the Birth of “The Onlooker”

Phillip Everett Caldwell’s journey into the world of art began with the creatures of his childhood imagination—particularly those drawn from horror and science fiction. The Alien franchise served as an early influence, igniting a fascination with bodily distortion, transformation, and fear. His early drawings were filled with nightmarish monsters, each infused with a raw energy that hinted at deeper psychological themes. Despite encouragement from art teachers throughout his youth, he would temporarily drift from this creative impulse as adulthood took hold. Still, the impulse to create never truly disappeared—it simply waited for the right moment to reemerge.

That moment came unexpectedly through a piece titled Blame. Initially conceived as a casual ink sketch, it found emotional resonance with a friend, sparking something inside Caldwell that had long been dormant. It was this piece that convinced him art could serve as a meaningful vessel—not just for self-expression, but for emotional transmission. He began to explore its themes further, evolving the original drawing into a digital form and eventually introducing a recurring figure known as “The Onlooker.” This character—developed through spontaneous, stream-of-consciousness drawing—became a central figure in his practice, a quiet observer within his chaotic visual universe. The piece eventually earned a special recognition award from an online platform, affirming its impact beyond Caldwell’s immediate circle.

“The Onlooker” is more than just a character; it embodies Caldwell’s conceptual approach. This silent figure appears repeatedly across his body of work, its presence both grounding and ambiguous. Sometimes appearing curious, other times sorrowful, the character encapsulates the tension at the heart of his visual language. It mirrors the artist himself—a witness to inner and outer monstrosities, never entirely at ease, never quite belonging. Through this figure, Caldwell constructs an emotional continuity across his pieces, giving his disjointed and surreal imagery a subtle, persistent center. It is this blend of spontaneity and recurring symbolism that forms the spine of his evolving style.

Drawing the Darkness Out

Influence in Phillip Everett Caldwell’s work rarely appears in neat citations or direct references; instead, it is absorbed and reconfigured into something uniquely his. Artists like H.R. Giger and Guillermo Del Toro, along with titles such as Cabinet of Curiosities, provide visual and thematic inspiration, particularly in their willingness to explore unsettling subject matter with precision and artistry. Video games such as Bloodborne, known for their atmospheric horror and richly textured lore, strike a deep chord with Caldwell. These cultural touchstones awaken something primal within him—a visceral urgency to make sense of his own emotional scars through a similar visual intensity.

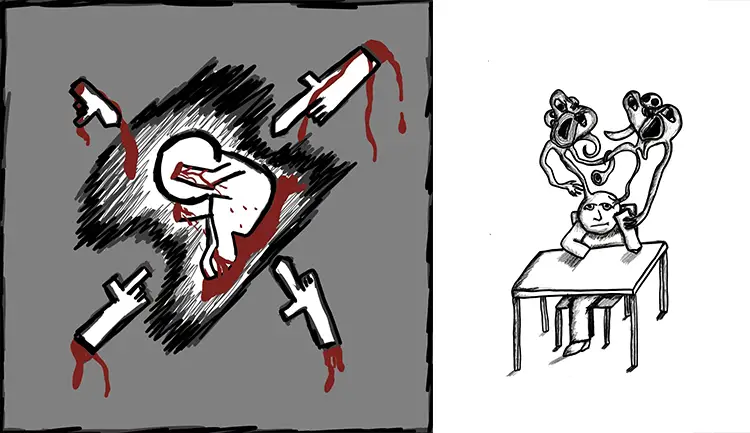

But Caldwell’s work is not simply an homage to horror or fantasy. His creative motivations are rooted in personal struggle and psychological exploration. Having endured significant hardships, he views art as a vehicle for emotional alchemy—a way to transmute painful experiences into forms that are simultaneously disturbing and beautiful. He is less interested in creating fantasy for its own sake and more committed to capturing the emotional weight of survival. The grotesque, in his hands, becomes a form of truth-telling. It strips away politeness, presenting the viewer with raw emotional forms shaped by chaos, grief, and introspection. There is a sense that these distorted beings are not meant to frighten, but to communicate something unspeakable.

This philosophy guides Caldwell’s working process. While he aims to complete a piece each day, he balances spontaneity with structure. Often beginning with pose studies, he transforms realistic foundations into bizarre anatomical fusions, pushing bodies into impossible configurations. The resulting figures—neither human nor machine, neither monster nor man—speak to his fascination with ambiguity. Their grotesque qualities are deliberate provocations, inviting the viewer to examine their discomfort. Each drawing becomes a battleground between discipline and impulse, offering a glimpse into a mind that constantly questions the border between internal darkness and external form.

Phillip Everett Caldwell: Sculpting Paradox with Pen and Pixel

Phillip Everett Caldwell’s artistic style thrives on contradiction. His work fuses surrealist figuration with grotesque biomorphism, creating hybrids that resist easy categorization. Influences from Outsider Art, Pop Surrealism, and early surrealist automatism are evident, but Caldwell’s voice is unmistakably distinct. His creatures are unsettling not just for their appearance but for their ambiguity: are they praying or writhing? Laughing or screaming? Each piece invites multiple readings, encouraging the viewer to linger in discomfort. The uncertainty becomes the message, a metaphor for the emotional and existential confusion that defines much of modern experience.

His preferred aesthetic is marked by sharp black-and-white contrasts that lend his compositions a stark, almost print-like intensity. With exaggerated anatomical features—twisted limbs, oversized eyes, jagged openings—he creates figures that feel simultaneously familiar and alien. These are not characters in a narrative, but archetypes of emotion and sensation. Despite their surreal distortion, they convey recognizable gestures: a hunch that suggests shame, a gaze that implies accusation, a posture that hints at yearning. These emotional traces give the work a human center, even when the figures themselves appear utterly otherworldly.

Texture plays a critical role in Caldwell’s visual vocabulary. Through dense hatching, rhythmic linework, and layered chiaroscuro, he creates a tactile surface that evokes skin, muscle, or even decaying material. Yet these textures never strive for realism. Instead, they function as symbolic evocations—suggesting vulnerability, violence, or transformation. The grotesque becomes beautiful not because it is sanitized, but because it is so thoroughly expressive. Caldwell’s creatures are not illustrations of nightmares; they are emotional conduits. They stand as visual riddles, unresolved yet deeply affecting, rendered with both restraint and an unflinching eye for the bizarre.