“If you arm were cut off, would that severed arm still be you? If a tiger ate that arm, would it still be you?”

Between Time and Identity

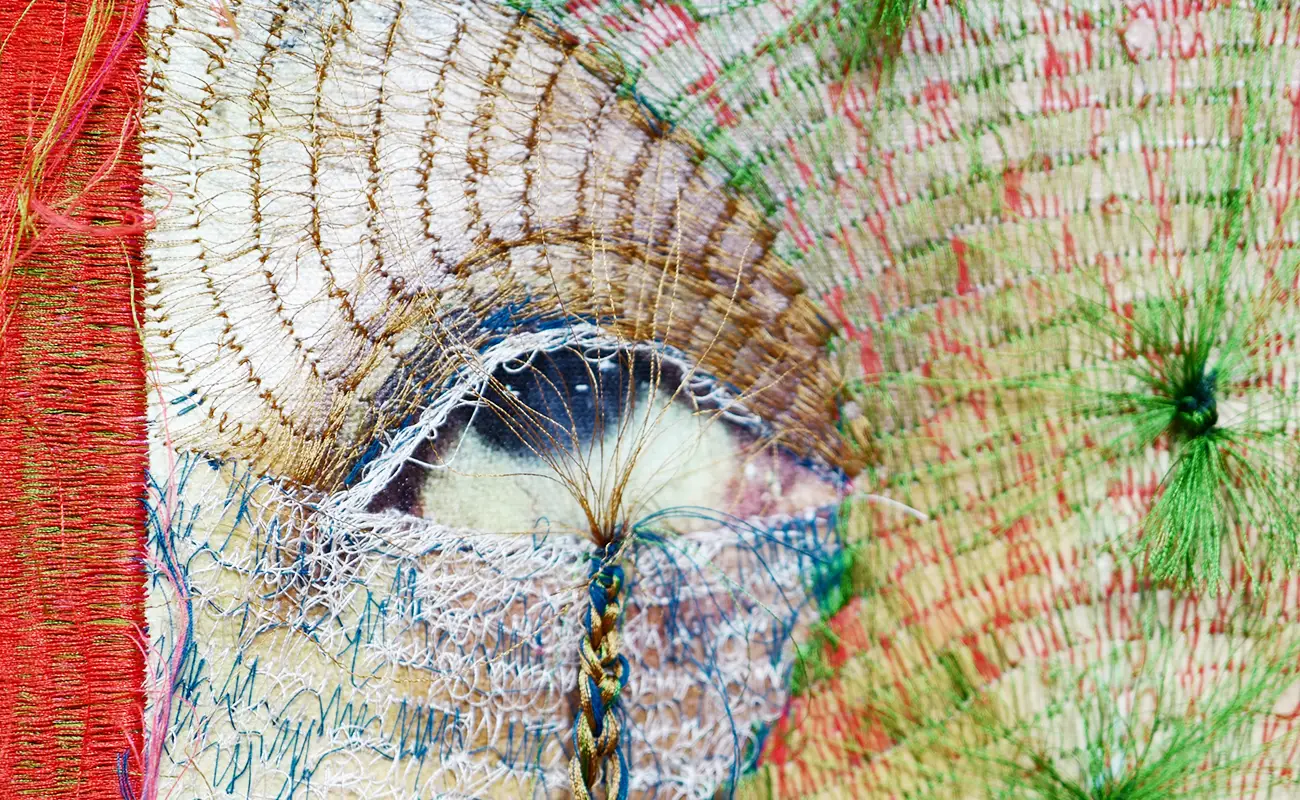

In the city of Daejeon, South Korea, Yoon Ji Seon has cultivated an artistic practice that is as deliberate as it is probing. Known for her ability to navigate across photography, painting, sculpture, and textile, she resists confinement to a single medium. Her celebrated Rag Face series exemplifies this boundary-crossing spirit, where photographs of her own face are stitched over with muslin and thread, blurring the lines between image and tactile surface. The act of sewing, both repetitive and contemplative, disrupts the flatness of photography while embodying the passage of time. It is here that she transforms questions of identity and the female body into something both visually fractured and deeply human.

For Yoon, the creative process is not about finding answers but about sustaining questions. Her life in a city with an unhurried rhythm mirrors the patience required by her work. The slower pace allows her to embrace uncertainty, contradictions, and moments of incomprehension. These elements become not obstacles but the very fuel for her creations. Art, in her hands, emerges as a series of visual inquiries, each layer of fabric and photograph confronting the elusive nature of existence.

This questioning extends far beyond her immediate environment. She looks outward to the broader world, where cultural differences, human interaction, and the unpredictability of nature provide new dimensions to her exploration. Living as someone who describes herself as slow and even clumsy within a rapidly changing society, she transforms her perceived limitations into an artistic strength. Every stitch, every photographic layer becomes a meditation on what it means to live in flux while remaining present within one’s body and time.

Rag face #18005, front and back, 194 × 111 cm, Sewing on fabric and photography, 2018

Yoon Ji Seon: Confronting Grotesque Beauty

Her artistic journey began in striking defiance of convention. When she presented her first solo exhibition, she expected it might also be her last. The works, which included implanting hair into pig bones and attaching ostrich feathers to chicken feet, startled audiences who had never encountered such raw transformations of organic matter. Many recoiled at the grotesque quality, yet it was precisely this discomfort that became a catalyst for her career. She began to question why society accepts eating meat without hesitation but reacts with unease when bones are reimagined as art.

That line of inquiry propelled her forward into further experimentation. Each work became an extension of curiosity, a visual response to contradictions between cultural practices and visceral reactions. Over time, her art evolved into complex engagements with philosophical thought and social constructs. Themes of identity, wordplay, and human perception emerged, informed by a Buddhist monk’s haunting question from her youth: if a severed arm becomes part of something else, does it remain you? This paradox, echoing the Ship of Theseus, became central to her work, pushing her to probe the fragile boundary between body, self, and transformation.

Wordplay enriches her artistic strategies, often guiding her material choices. By merging Korean idioms about impossibility and unforgettable impressions, she created works implanting her own hair into animal bones, literalizing abstract concepts. Over time, her practice expanded into series such as Pricked, where piercing photographs became a method of questioning visibility and erasure. The grotesque and the poetic collide in her creations, yielding works that remain unsettling yet profoundly thought-provoking. Her art is not designed to soothe but to agitate, compelling viewers to reconsider their own assumptions about material, body, and meaning.

Rag face #18010, front and back, 154 × 143 cm, Sewing on fabric and photography, 2018

Dialogues with Ancestors and Materials

Among her diverse body of work, one piece that continues to hold deep significance is her intervention into the 1710 self-portrait of her ancestor, the painter Yoon Du-seo. By implanting her own hair into the eyes of this historical reproduction, she created a layered confrontation with heritage, gender, and identity. The painting, which once represented the patriarchal authority of her family, became a site of rebellion as well as reconciliation. For her, this gesture bridged centuries of lived experience, simultaneously challenging restrictive traditions while offering a form of healing across time.

This act exemplifies her broader interest in transforming materials into carriers of philosophical dialogue. While many of her works explore the body through hair, thread, and bone, she also seeks unfamiliarity in the familiar. Her recent exhibition, Manufactured Desire: I, Who Dream of You, introduced small-scale butterflies made from shrink plastic, a material associated with children’s crafts. Displayed against a backdrop of traditional Chinese butterfly-wing arrangements symbolizing prosperity and longevity, the installation staged a confrontation between cultural ideals and ecological realities. The butterflies’ fragile presence questioned the contradiction of materials that carry both innocence and destruction.

Through this approach, Yoon highlights the precariousness of human desires and the contradictions embedded within material histories. Plastic, once invented to save elephants from ivory exploitation, now threatens ecosystems across the globe. By juxtaposing synthetic butterflies with sacrificial real wings, she transforms her installation into a stage where contradictory narratives coexist. This engagement with material history and symbolic transformation is not only ecological but also philosophical, urging viewers to reflect on what is overlooked, disregarded, or sacrificed in the name of human aspiration.

Rag face #24003, front and back, 187 × 238 cm, Sewing on fabric and photography, 2024

Yoon Ji Seon: From Stillness to Movement

While much of her practice has centered on the body as a static presence, Yoon has expressed an increasing interest in exploring motion. She envisions future projects that capture the body in time, not just as an object of inquiry but as a living agent of art itself. Her admiration for the works of Oskar Schlemmer and Pina Bausch reflects this desire to integrate movement into her practice. She contemplates how dance, performance, and lived time might infuse her work with a new dimension of vitality.

This evolution would mark a shift from her long-standing focus on material transformation into a broader dialogue with performance. Rather than stitching photographs or piercing surfaces, she imagines embodying art through gesture and temporal experience. Such an exploration could extend her investigations of identity into the dynamic space of lived action, where the body ceases to be a symbol alone and instead becomes an instrument of creation in real time.

Her artistic trajectory has always been one of questioning boundaries and resisting static definitions. Whether through grotesque reconfigurations of organic matter, delicate interventions into ancestral portraits, or installations that confront ecological contradictions, her work thrives on provoking new inquiries. The potential turn toward movement reflects her continued commitment to asking questions that are both personal and universal. In contemplating the body in motion, she continues her lifelong pursuit of art as a language for questioning what it means to exist.