A Sculptor of Systems and Subversion

Tom Sachs, a sculptor who reshapes the cultural lexicon through satire, engineering, and relentless DIY aesthetics, has carved a singular identity in contemporary art. Known for crafting hand-built versions of modern icons—ranging from lunar modules to McDonald’s counters—his work brims with contradictions: reverence for design paired with irreverent critique, structural integrity disguised as amateurism, and playfulness grounded in labor-intensive processes. Born in New York City in 1966, Sachs trained at the Architectural Association in London before earning his BA from Bennington College in Vermont. His work emerged during the 1990s with an audacious blend of bricolage and conceptual critique that propelled him into the spotlight. Whether using duct tape and foam core or bronze and Tyvek, Sachs places emphasis on the visible mechanics of making—elevating the idea that how something is made is as critical as what it represents.

Museums worldwide—from the Museum of Modern Art in New York to Centre Pompidou in Paris—house Sachs’ sculptures, installations, and objects. These pieces engage directly with the machinery of capitalism, mass production, and technological fetishism. Sachs’ approach borrows from both engineering labs and Dadaist absurdity, creating artworks that look like prototypes rather than polished artifacts. Yet this scrappy aesthetic is deliberate; his works are meant to wear their process like a badge, a core principle he’s enshrined in his studio’s operational ethos. His sculptures often foreground their screws, joints, and adhesives, favoring exposure over concealment. Rather than striving for perfection, Sachs champions the honest mark of effort—what he calls “the scars of labor.”

Among the recurring themes in his practice is a fascination with American consumer culture and its intertwining with identity, power, and aspiration. From sculpted Chanel guillotines to reimagined Prada death camps, Sachs reconstructs elite symbols through humble, tactile materials, inviting the viewer to reconsider luxury, branding, and mass culture. These ironic remixes are not simply critiques; they often reflect Sachs’ own obsessions and desires. His reconstructions of things he admires—be it Le Corbusier’s architecture or NASA’s spacecraft—speak to an artist who is both critic and devotee, someone who believes making something by hand is an act of personal ownership and transformation.

Tom Sachs: The Blueprint of Resistance

Sachs’ early studio, Allied Cultural Prosthetics, embodied his ethos: the belief that modern life had substituted real culture with artificial stand-ins. That name set the tone for works that would turn familiar icons into strange, sometimes disturbing hybrids. His controversial 1994 display for Barneys New York—a Hello Kitty Nativity—recast sacred imagery with corporate mascots, provoking outrage and acclaim in equal measure. The Virgin Mary became Hello Kitty, the Three Kings morphed into Bart Simpsons, and the crèche bore a golden McDonald’s arch. This act of branding the sacred was more than provocation; it laid bare the machinery of cultural commodification and Sachs’ unique ability to remix it into new, jarring configurations.

From fashion weapons like the Tiffany Glock and Hermès Hand Grenade to more unsettling juxtapositions like Prada Deathcamp, Sachs blurred the line between consumer product and cultural critique. These works from the 1990s highlighted his evolving interest in luxury branding’s complicity in systems of violence and power. While often constructed from non-functional materials—tape, foam, packaging—Sachs occasionally crossed into real-world impact. One such example is Hecho in Switzerland (1995), a working handmade gun that Sachs and his team replicated and sold back to the city of New York during gun buyback programs. This oscillation between art object and functioning weapon underscores the artist’s commitment to collapsing the distance between idea and action.

After a poorly received outsourced sculpture, SONY Outsider, Sachs recommitted himself to hand-built processes, rejecting perfectionism in favor of visible craftsmanship. This turning point prompted a renewed focus on bricolage—assembling objects from repurposed materials into structures with new meaning. His exhibition American Bricolage at Sperone Westwater in 2000 curated artists who shared this philosophy. Sachs developed an in-studio discipline around the practice of knolling—systematically arranging tools and materials at right angles—originating from his time in Frank Gehry’s shop. This visual organization wasn’t just functional; it symbolized his entire approach to creativity: clarity through structure, and the beauty of systems laid bare.

From Duct Tape to Deep Space

Sachs’ deep fascination with space travel has shaped some of his most iconic works, culminating in the ongoing Space Program series. Beginning with handmade lunar modules and space suits, the project exploded in scale by 2007 with a full-scale Apollo-style mission staged at Gagosian Gallery in Los Angeles. This installation featured a mission control deck outfitted with 29 closed-circuit monitors, a lunar lander, and astronauts armed with shotguns. Humor and absurdity punctuated the mission—vodka bars and almanacs replaced NASA’s clinical precision—while Sachs’ handmade aesthetics stood in stark contrast to the sterile perfection of actual aerospace engineering. Here, he suggested that imagination, human error, and playful ambition were as valuable as technological mastery.

Later editions of the Space Program took audiences further into Sachs’ alternative cosmos. Space Program: Mars, staged at the Park Avenue Armory in 2012, included inventions for surviving life on the red planet, from a poppy-based terraforming system to solar-powered boomboxes. Audiences weren’t just observers; they became participants in Sachs’ performative simulation of interplanetary colonization. By embedding his handcrafted sculptures within immersive environments, Sachs reframed the idea of exploration—not as conquest, but as an iterative, messy, and deeply human process. Each artifact, from foamcore satellites to 3D-printed gear, reinforced his belief that making things is a form of thinking.

These fantastical missions extended to Space Program: Europa in 2016 and Space Program: Rare Earths in Hamburg by 2021–2022. Yet beyond the humor and spectacle, Sachs’ space-themed installations explore the seduction of technological optimism and the persistence of Cold War-era dreams in the collective psyche. Deborah Cullinan noted that his space projects resurrect the utopian ideals that once fueled public fascination with NASA, while also reminding viewers how quickly those dreams become enmeshed in commerce and spectacle. Sachs’ works operate as both tribute and critique, embracing the wonder of invention while dismantling the myths that surround progress.

Tom Sachs: Studio Doctrine and Cultural Fallout

Integral to Sachs’ philosophy is the belief that effort should remain visible, that failure is part of the creative process, and that structure breeds innovation. This has manifested in his workshop’s internal codes, most notably in 10 Bullets, a video-manifesto detailing the studio’s rules. Among them: “Always Be Knolling”—a directive to keep the workspace hyper-organized—and “Work to Code,” insisting that each member follows Sachs’ procedural logic. These principles, born from his years in Gehry’s studio, were intended to establish rigor and discipline. Yet this same intensity later came under scrutiny, as former employees described the studio as cult-like, citing manipulation, psychological strain, and harsh working conditions.

In 2023, media investigations surfaced allegations that Sachs had fostered a toxic work culture. Reports from past staff members pointed to emotional coercion and public humiliation, describing the environment as “fear-inducing” and “manipulative.” Despite Sachs’ emphasis on transparency in art, this behind-the-scenes controversy cast a long shadow over his brand. Nike, with whom Sachs had collaborated on the Mars Yard sneaker and its successor, the General Purpose Shoe, expressed public concern following the accusations. The company distanced itself after removing controversial phrases from packaging and acknowledged an ongoing review of its relationship with the artist.

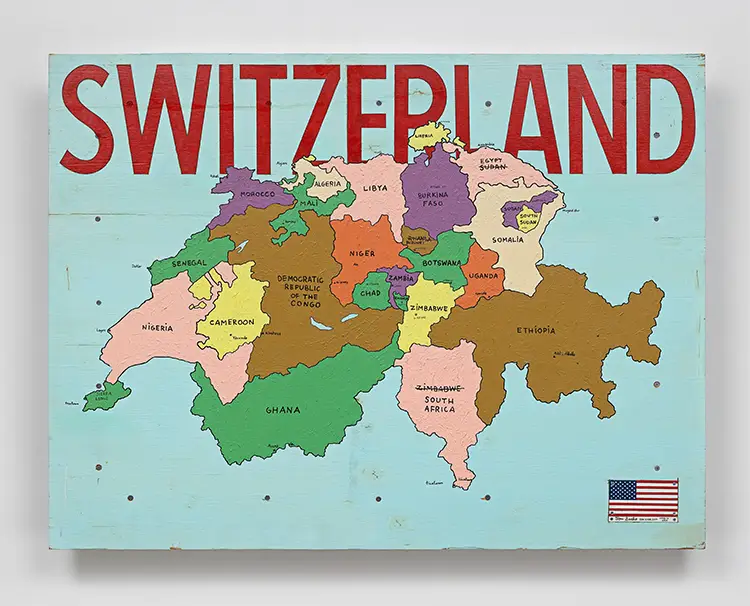

Still, Sachs’ impact on contemporary art remains indisputable. His reimagining of the Japanese tea ceremony—first exhibited at the Noguchi Museum and later the Nasher Sculpture Center—infused centuries-old tradition with modern irreverence, complete with handmade utensils and a plywood tea hut. Other installations, like his Swiss Passport Office, tackled global anxieties around citizenship, migration, and bureaucracy. Across decades and media, Sachs continues to provoke, enchant, and complicate. While his personal conduct remains a topic of debate, the body of work he has assembled tells the story of an artist unafraid to dismantle systems—cultural, industrial, or celestial—and reassemble them into something raw, bizarre, and profoundly original.