“Painting isn’t about depicting something external but creating a space that feels internally real—something you can think through and feel at the same time.”

Spaces Within and Without

Sharon Yaoxi He’s work operates at the intersection of visual perception and introspective exploration, inviting viewers into a world where inner experience and constructed imagery collapse into each other. A Chinese-Canadian painter based between New York and New Jersey, He weaves her cross-cultural upbringing into each canvas. Born in China and raised in Vancouver from the age of six, she brings a bicultural sensitivity to her art—one that constantly questions how identity, place, and memory coalesce through perception. Her academic journey, from earning her BFA at Emily Carr University to completing an MFA at Columbia University, further sharpened her conceptual grounding and deepened her philosophical inquiries into space and cognition.

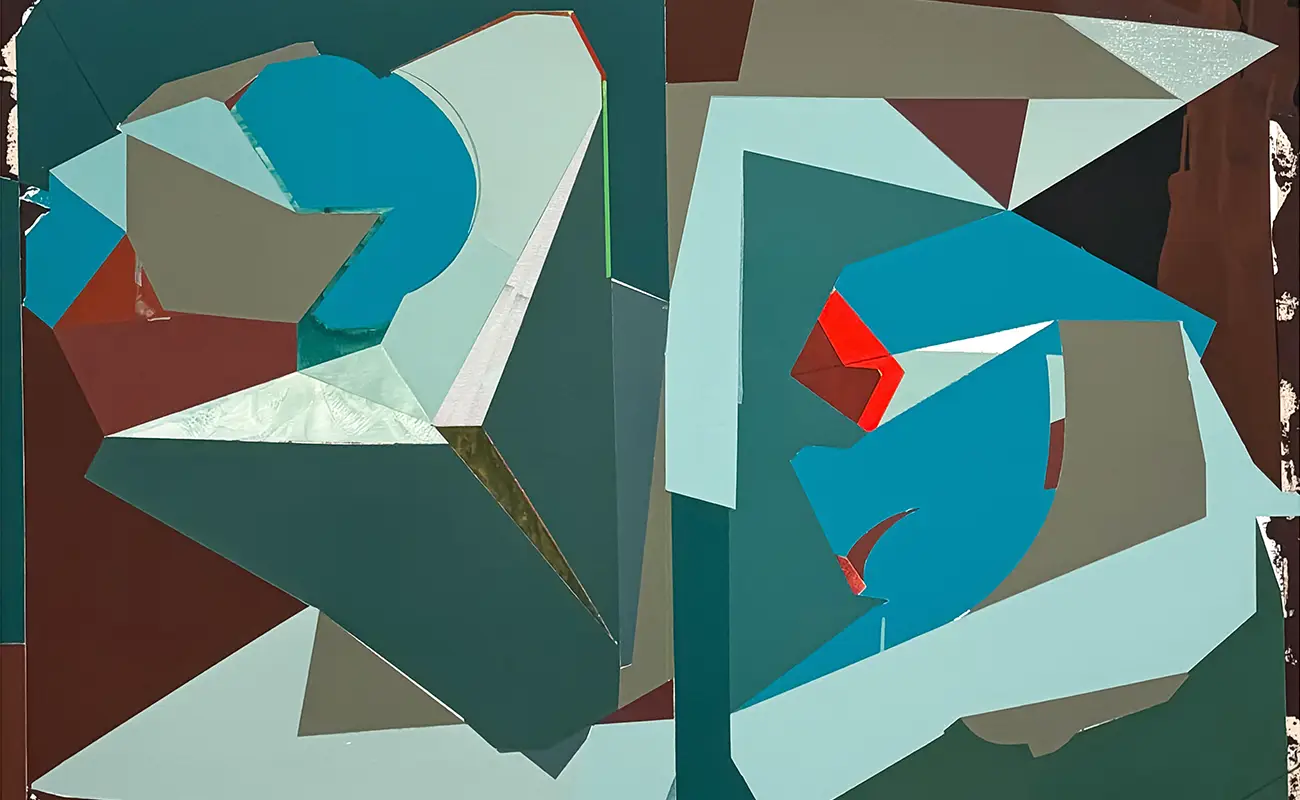

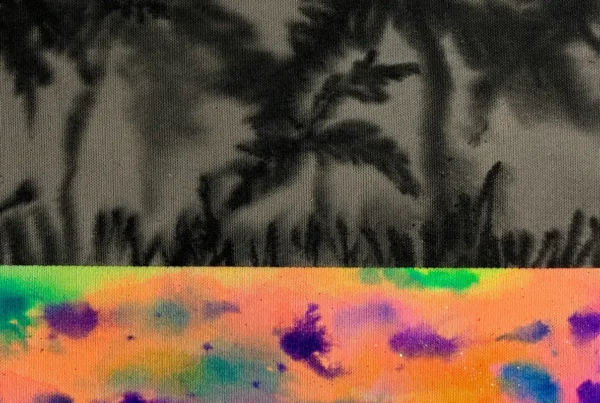

He’s paintings do not merely portray external scenes; rather, they create spatial experiences that originate from within. Her visual language reflects a synthesis of Chinese landscape painting techniques with Western philosophical thought, especially Immanuel Kant’s concept of space as subjective. Through fluid compositions and layered perspectives, she challenges the viewer’s sense of dimensional stability, guiding them through spaces that shift with memory and emotional resonance. These visual strategies become vehicles for exploring time—not as linear progression but as a felt, psychological continuum. He’s work isn’t concerned with realism in a traditional sense; instead, she constructs perceptual spaces that feel psychologically vivid, as though painted with both mind and hand.

At the heart of her practice is a deep interest in how attention, cognition, and emotion intersect within the act of seeing. She investigates the boundaries between the mental and the physical, creating artworks that invite both contemplation and emotional engagement. The resulting canvases are not windows into other worlds but rather frameworks for self-reflection, places where viewers are encouraged to consider how their own histories and cognitive patterns influence what they perceive. In this way, He’s paintings become more than visual objects—they are participatory spaces, offering a dialogue between artist, medium, and viewer.

Sharon Yaoxi He: Painting as Psychological Terrain

Rather than adhering to any fixed style, Sharon Yaoxi He’s approach to painting is driven by her intellectual curiosity and personal introspection. Her work is rooted in the psychological experience of space—how memory and cognition shape perception—and her method often involves compositional experimentation. She manipulates spatial constructs such as vanishing points, perspective shifts, and layered imagery to destabilize the viewer’s visual expectations. These formal devices are not simply stylistic choices but serve as tools to evoke a deeper mental engagement with the artwork. Through this practice, He pushes painting beyond surface aesthetics into the territory of embodied thought.

The conceptual architecture of her work frequently draws from traditional Chinese aesthetics while integrating modern Western philosophical ideas. She engages with the visual rhythm of Chinese landscape painting, with its flowing perspectives and attention to negative space, and fuses these techniques with an investigation into how space is mentally organized. Influences such as Kant’s notion of subjective space inform the theoretical framework that underpins her compositions. In doing so, He is not attempting to reconcile East and West in any didactic way; rather, she explores how the friction and harmony between different cultural logics can produce a richer visual and emotional language.

Despite the intellectual depth of her process, He’s practice remains grounded in the physicality of painting itself. She describes her engagement with the medium as intuitive, something that began as a spontaneous impulse rather than a career ambition. Her early fascination with the act of painting evolved into a structured discipline, shaped over time by an ongoing commitment to the medium. She never set out to become an artist in the formal sense—instead, her path unfolded organically as she followed the internal demands of the work. This orientation toward the process itself over outcomes continues to guide her practice, making each painting a direct extension of thought, emotion, and attention.

The Shape of Focus

Creating the conditions for focused work is an essential part of Sharon Yaoxi He’s studio routine. She begins each session by thoroughly cleaning her workspace, both at the beginning and end of the day. This ritual isn’t merely about organization—it functions as a mental reset, signaling the transition into and out of the concentrated state required for painting. Within this environment, she enters what she describes as a flow state, during which she becomes fully absorbed in the work. Her focus remains sharp for several hours, after which she deliberately stops painting, respecting the natural arc of her concentration. This measured approach not only preserves the integrity of her attention but also maintains a sense of clarity and intention within her practice.

He’s rhythm in the studio reflects her broader respect for the inner processes that inform artistic creation. She avoids forcing productivity and instead aligns her working habits with the psychological demands of her art. This alignment ensures that her practice remains not only sustainable but also deeply connected to the internal states she seeks to articulate through painting. Rather than pushing herself to work through mental fatigue, she allows space for rest and reflection, trusting that these intervals are just as integral to the process as the moments of active creation. Her discipline lies not in output but in her sensitivity to when and how she engages with the work.

The tactile intimacy of painting continues to draw her back, even as she has explored other mediums. While she has experimented with ceramics and installation, she finds painting to be the most immediate and resonant form of expression. The connection between hand, surface, and image offers a directness that supports the psychological depth she seeks in her work. Nevertheless, she remains open to the possibilities that other materials might offer in the future. Ceramics, in particular, remains an area of interest—one she may explore more seriously, either as a complement to her painting practice or as a separate endeavor altogether.

Sharon Yaoxi He: Memory, Influence, and the Invisible Archive

Sharon Yaoxi He approaches her artistic influences not as fixed icons but as evolving conversations. In her earlier years, she gravitated toward modernists such as Kandinsky and Mondrian, captivated by their formal investigations and use of abstraction as a visual language. The structure and clarity of the Bauhaus movement also played a significant role in shaping her understanding of composition and form. These influences provided her with a foundational framework that emphasized precision, balance, and conceptual rigor. However, her sources of inspiration have shifted as her practice has matured, reflecting her expanding interests and changing intellectual focus.

More recently, He has found profound resonance in the work of Wu Guanzhong, whose synthesis of traditional Chinese art and modernist abstraction mirrors some of her own inquiries. Wu’s ability to express emotional nuance and spatial complexity with elegance and restraint speaks to He’s own pursuit of subtlety and layered meaning. Beyond the visual aspects of Wu’s work, his writings have offered her a model of intellectual clarity paired with poetic insight. His example reinforces the possibility of merging rigorous thought with visual sensibility, encouraging He to continue navigating between intuition and analysis in her own practice.

When reflecting on individual pieces, He resists the idea of assigning singular significance to any one work. For her, each painting is a temporal marker, an index of the mental and emotional landscape she inhabited during its creation. These works function almost as personal records—quietly mapping changes in thought and feeling over time. Her attachment lies not in the final product but in the process: the decisions, revisions, and fleeting moments of insight that occur while painting. Once completed, the piece becomes autonomous, and her connection to it shifts. What remains most meaningful is the invisible archive—the internal shifts and discoveries that take place in the making.