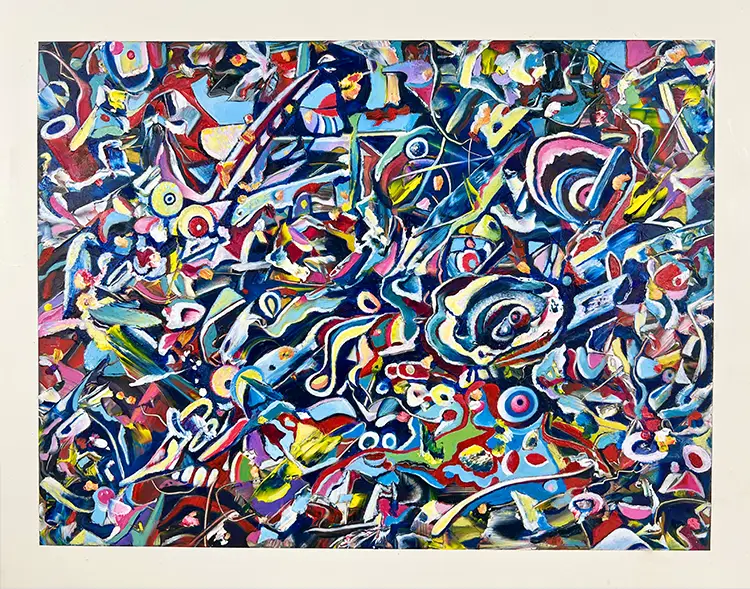

“I call what I do, Photorealistic Abstract Mindscapes.”

The Origins of a Visual Language

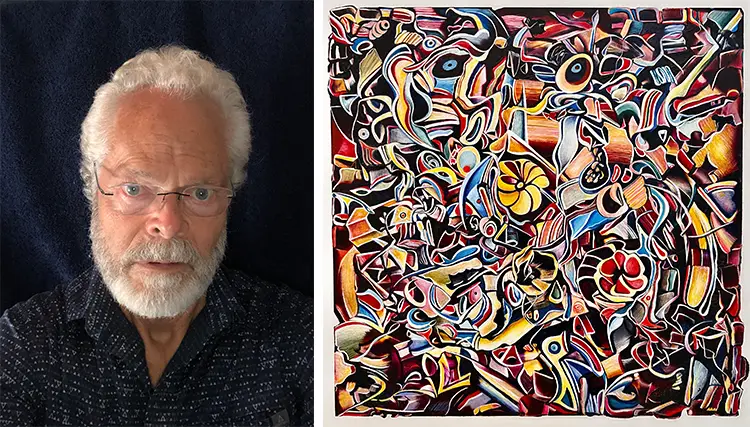

Standing at the intersection of memory, perception, and nature, R. Wayne Reynolds constructs visual narratives that resist conventional categorization. Born in Arlington, Virginia, on February 22, 1953, Reynolds was immersed in a rich cultural environment from a young age. His first visit to the National Gallery of Art at just five years old marked the beginning of a lifelong relationship with both art and the natural sciences. Frequent trips to the Smithsonian’s Natural History Museum deepened his appreciation for organic form, setting the stage for a creative path that continues to bridge observation and imagination. His early fascination with visual storytelling led him to earn a BFA in Painting from The Maryland Institute College of Art in 1975, but it was the experiential knowledge he accumulated outside the academic sphere that truly defined his artistic journey.

Reynolds’ upbringing played a central role in shaping his multifaceted approach to art. Influenced by a family rich in practical and creative wisdom, each member left a distinct imprint on his evolving identity as an artist. His sister, fifteen years his senior and a painter herself, became his first guide into the world of drawing. His father’s craftsmanship as a builder taught him the joys of construction, while his mother instilled a quiet, enduring patience that still informs the detailed aspects of his process. From his brother, a mentor in the realm of competitive sports, he learned how to channel intensity and focus into every pursuit. These layered influences converge in a practice that celebrates both the physicality and philosophical weight of artmaking.

Reynolds’ path to professional artistry weaves through diverse creative terrains, including his expertise in gilding restoration—a centuries-old technique of applying delicate sheets of gold leaf. His early job in a custom framing shop developed into a specialized business that served museums, collectors, and galleries. During a formative four-year tenure at the National Gallery of Art’s Conservation Department, he encountered masterpieces from every corner of art history. One unforgettable moment—holding Leonardo da Vinci’s Ginevra de’ Benci in his hands—resonated deeply and would later inspire his venture into interactive art. Works like Land of Plenty, featured on his website, reflect this commitment to engaging viewers not just visually but physically, inviting them to become participants in the artistic process.

Left: R. Wayne Reynolds, Right: Life is Full of This and That Oil

R. Wayne Reynolds: Constructing the Photorealistic Abstract

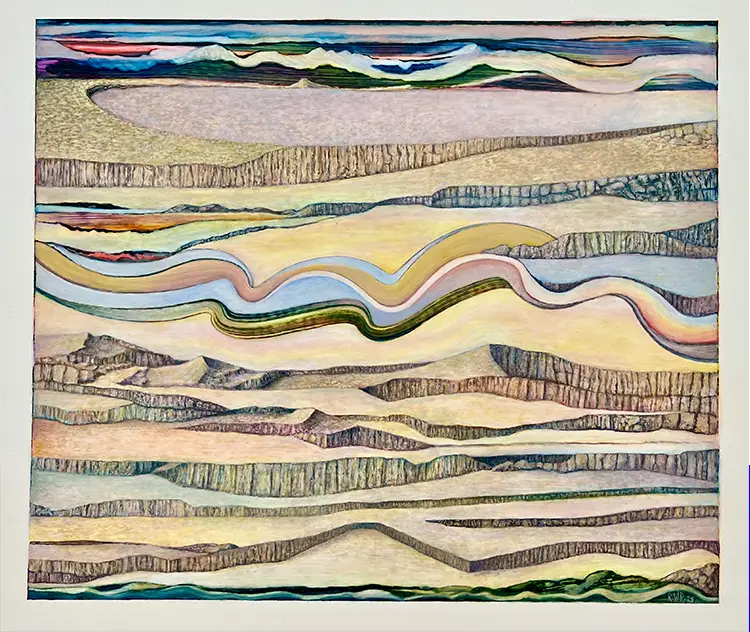

At the core of Reynolds’ work lies a unique concept he calls “Plein Air Mindscapes”—a term that encapsulates his distinctive deviation from traditional landscape painting. While rooted in observational study of the natural world, his compositions evolve into abstract expressions that transcend any specific location or biological accuracy. Instead of replicating scenery, he reconstructs it from memory, distorting dimension and species with unapologetic freedom. His approach resists linear interpretation, emphasizing the use of color, form, and spatial composition as autonomous elements that communicate psychological rather than physical truths. The result is a body of work that achieves a remarkable synthesis: at once photorealistic in its technical precision and abstract in its conceptual intent.

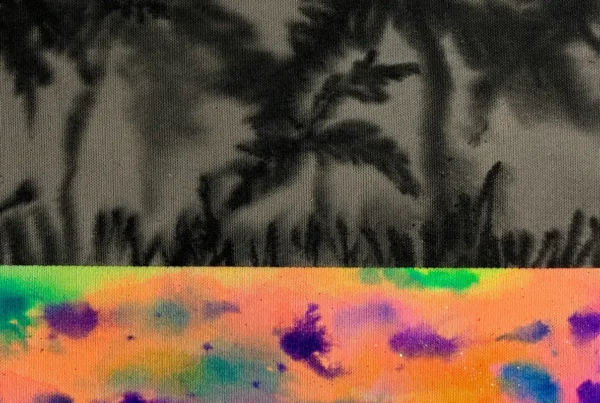

This signature style is not a product of accident but of a deliberate merging of artistic disciplines and historical traditions. Reynolds draws influence from a wide spectrum of movements, integrating the finesse of the Old Masters, the chromatic strategies of the Impressionists, and the fractured perspectives of Cubism. From the Abstract Expressionists, he borrows emotional intensity, while the Surrealists lend him their fascination with interior worlds. These varied influences do not simply coexist in his work—they converge into a unified language that continuously evolves through risk-taking and experimentation. He intentionally seeks out unfamiliar materials, relying on spontaneity and discovery to expand the limits of his practice.

Despite his experimental ethos, Reynolds maintains a disciplined control over his creative output. He prioritizes continuity and cohesion, allowing his artistic energy to lead the way while balancing intuition with experience. Patience plays an instrumental role in his process, allowing each composition the time it needs to fully articulate itself. He sees his studio not as a place constrained by routine, but as a stage for improvisation governed by structure. This equilibrium—between chaos and control, memory and invention—is what gives his work its distinct emotional weight and technical clarity. Every piece he produces is part of a larger conversation, a visual dialogue that challenges viewers to reconsider their perceptions of realism and abstraction.

Utah and the Colorado River

The Intersection of Art and Experience

Reynolds’ artistic philosophy finds its most compelling expression in pieces that blur the boundary between observer and participant. His standout work, My Reality is Virtual—a large-scale black-and-white acrylic painting measuring four by six feet—embodies the essence of his creative inquiry. Completed in 2022, the piece has garnered widespread acclaim, appearing in his solo exhibitions at Art Basel Miami and New York City, where it was featured in a show titled 50 Years, R. Wayne Reynolds. Praised by Artforum as a “Must See,” the painting encapsulates his masterful handling of contrast, structure, and psychological depth. It invites viewers to confront the duality between the organic and the artificial, encouraging a reexamination of what it means to perceive reality through the lens of memory.

His experiments with interactive artwork, such as the kinetic piece Land of Plenty, further highlight his desire to expand the viewer’s role in interpreting a painting. These works are not static; they invite touch, movement, and exploration. By embedding physical engagement into the experience of art, Reynolds dissolves the traditional barriers between artist, artwork, and audience. This innovation is not just technological—it’s philosophical. It asks the audience to take ownership of the visual narrative, to shape meaning in collaboration with the artist’s vision.

Reynolds also envisions a future where the very source of light becomes a medium. One of his long-term aspirations involves using sunlight as an active component in the creation of paintings. His current research and working sketches aim to transform solar energy into a tool for producing visual imagery, pushing the boundaries of traditional media even further. This pursuit aligns with his lifelong exploration of how natural phenomena can inform and expand artistic technique. Whether he’s working with gold leaf, acrylic, or pure sunlight, Reynolds continues to search for new ways to deepen the relationship between art, environment, and viewer.

EDIT TEXT 3

Storm Clouds Forming

R. Wayne Reynolds: A Practice Built on Precision and Intuition

In the studio, Reynolds is guided by a singular requirement: uninterrupted time. The absence of distractions is not dependent on silence or isolation, but on the presence of an open window of creative opportunity. Once immersed in that space, he finds that concentration arrives naturally. His workspace is an orchestration of materials and ideas, where the harmony of elements is more crucial than any physical arrangement. Each tool has its function, but the real instrument is his own intuitive rhythm. He describes his practice as being akin to conducting an orchestra, with each medium representing a different instrument under his command.

Over the years, he has explored an expansive variety of materials, choosing them not for familiarity but for their capacity to express new ideas. Whether working with canvas, metal, gold leaf, or digital interactivity, Reynolds refuses to be confined by a single technique. This adaptability not only fuels innovation but also ensures that every artwork speaks in a fresh voice. The materials themselves become collaborators in the creative process, reacting and responding to his guidance with unexpected results. For Reynolds, mastery means not control, but a willingness to listen to what each element wants to become.

Even as his techniques diversify, the conceptual foundation of his work remains steadfast. He is committed to expressing what he calls “the diversity of precision, color, and form found in the natural world.” That commitment is not rooted in imitation but in translation—translating lived experience, emotional memory, and visual knowledge into a language that others can engage with. His practice is a continual negotiation between discipline and spontaneity, between the structure of art history and the unpredictable currents of creativity. This ongoing dialogue, shaped by both vision and experience, is what allows Reynolds to transform his inner landscapes into works that resonate far beyond the canvas.