“I like when an image feels believable, but not entirely possible.”

Where Stillness Meets Intensity

Juan Carlos Beltrán’s work dwells in a place at once grounded and imagined, where reality and fiction coexist in images that feel almost too vivid to be real. Born in 1991 in Culiacán, Mexico, Beltrán builds his visual language through a synthesis of photography, architecture, and generative AI. His unique background in business and analog photography informs a practice that is as strategic as it is instinctual, rooted in rhythm and repetition.

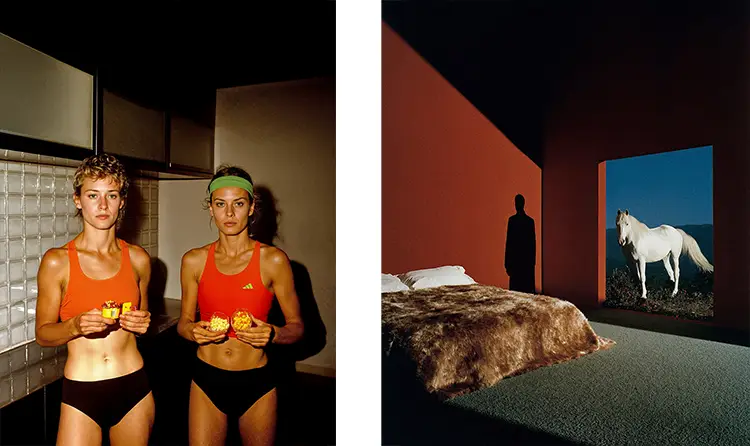

Juan Carlos Beltrán collaborated with Hermanos Koumori on To Be a Runner is to Be an Artist, a conceptual capsule for Art Week Mexico City that explored running through a visual and artistic lens, blending analog, photographic, and AI-driven techniques with references to athletics, technology, nostalgia, and personal narrative. He has also worked with ATRA, a leading design studio based in Mexico City; Bang & Olufsen; Apple; and Tiffany & Co., as well as designing the Scielo MX wine label collection for Rivero González. Through these partnerships, his visual work has been showcased by brands at major international art fairs such as ZⓈONAMACO and Art Basel, extending his presence across North America and Europe. Beltrán also presented Lo que resiste at Abierto Mexicano de Diseño CDMX, exhibited at Centro de Cultura Digital. In addition, he has contributed to a significant large-scale North American project alongside prominent figures in contemporary art, emphasizing the versatility and reach of his multidisciplinary practice.

Growing up in the distinctive landscape of Culiacán shaped his visual sensibility in both intimate and structural ways. The city’s contradictions — chaotic yet calm, brash yet deeply poetic — offer a blueprint for his artistic inquiry. A walk down a street might present a soundtrack of banda music, followed moments later by the serenity of James Turrell’s Skyspace at Jardín Botánico Culiacán. This friction — rawness and beauty — permeates Beltrán’s work. He draws from a specific visual vocabulary: concrete silhouettes reminiscent of Félix Candela’s modernist curves, sacred symbols tucked into daily life, and greenhouse lines slicing the rural periphery with machine-like precision. Beltrán’s approach reflects a fascination with the halfway point — between control and randomness, permanence and transience. Photography remains the medium through which he anchors his work in the real, while architectural references provide form and structure. Rather than treating AI as a visual effect, Beltrán uses it as a conceptual instrument to examine memory, perception, and the tension between authenticity and imagination. This fusion results in artworks that straddle time and place, evoking memories that feel universal but remain anchored in a very personal sense of geography and light.

The Discipline of Vision

Art entered Juan Carlos Beltrán’s life through a moment of chance. At thirteen, during a family trip, he picked up a neglected camera and discovered how photography could slow perception. What began as a curiosity gradually evolved into a deeply intentional pursuit of visual storytelling. Though he initially studied Business Administration in Boston, his artistic training took shape later at UCSD in San Diego, where he immersed himself in film photography, darkroom processes, and the patience of analog.

Upon returning to Mexico, Beltrán took a full-time role in his family’s agricultural business. This shift did not sideline his creative ambitions — it reshaped them. The systematic nature of agricultural planning — its cycles, repetition, and constant calibration — became a structural metaphor for how he sees and creates images. Patience, repetition, and attentive control became not just agricultural principles, but artistic ones—now shaping how he works with light and form.

At the core of Beltrán’s practice lies an interest in dualities. His imagery often resides in liminal spaces, where moments feel neither fully spontaneous nor entirely constructed. He avoids a polished, idealized perfection, favoring instead a visual language that feels earned and honest. Whether working with photography, architectural imagery, or AI-generated scenes, Beltrán prioritizes emotional truth — even when that truth emerges from constructed imagery. This pursuit of honesty over artifice ultimately defines his style.

Memory in Design, Emotion in Structure

Part of Beltrán’s visual philosophy has been shaped by architects who explore the emotional force of material, space, and experience. Lina Bo Bardi, Teodoro González de León, and Oscar Niemeyer inform his sense of how architecture can hold memory and feeling. In photography, he draws inspiration from photographers such as Harry Gruyaert and Alex Webb, whose color-drenched street scenes sit at the edge of chaos. Yet no influence is as foundational as the light of his hometown. Culiacán’s harsh, golden atmosphere infuses his visual narratives with a clarity that is both formal and affective.

This light is not merely a backdrop but an active presence in his work. It reveals texture and truth, rendering imperfections visible and refusing to romanticize. Where other cities flatter or soften with ambiance, Culiacán exposes. That honesty becomes a conceptual framework for Beltrán: beauty and discomfort coexist, and both deserve to be seen. In his work, lighting is not decorative — it is an emotional climate-setting force.

These themes manifest strongly in Arriba y a la izquierda, a long-term series centered on subtle, everyday encounters in Sinaloa. The images rest in the quiet rhythm of life: a splash of sunlight across concrete, a waiting moment, an abandoned storefront. The series is not a documentary, but a visual poem built through repetition, stillness, and memory. His AI-driven work extends this sensibility into imagined interiors, such as in BÓVEDA (Los Ángeles, 2024), where ‘90s-tinted spaces feel half-remembered.

Between Daydreams and Design

The structure of Beltrán’s daily life mirrors the balance his work seeks: a negotiation between discipline and imagination. Mornings are spent managing logistics and operations within his family’s agricultural business in Sinaloa — a role marked by precision, responsibility, and focus. This grounded rhythm provides the mental scaffolding for his creative ideas to evolve. Outside of those hours, his artistic process shifts fluidly: some days are devoted to editing photographs, scanning negatives, or developing film; on others, he disconnects intentionally, letting stillness reset his eye.

Looking ahead, Beltrán continues to expand Arriba y a la izquierda while developing new AI-based projects that explore the emotional potential of architecture. His current ongoing interest lies in how silence, texture, and material can hold memory and longing. These new works blur geographic and temporal references, drawing as much from internal landscapes as from the places he has lived or imagined. For Beltrán, the aim is not to replicate a specific place, but to build a felt geography — a space between design and daydream, where fiction becomes a method for articulating what feels deeply personal and universally human.

“I’m drawn to images that feel like memories you’re not entirely sure ever happened.”