A Childhood in Colour: The Awakening of a Visual Listener

Jack Coulter’s first encounter with his extraordinary perception began in quiet moments that most would overlook. Growing up in Belfast, his earliest memory is of sitting in silence on his family’s sofa, intently focusing on the beat of his own heart. With eyes closed, instead of darkness, he was met with bursts of colour — vivid orbs pulsating in tandem with each thud. It was the start of a lifelong experience that would come to define both his identity and his creative purpose. Diagnosed with synaesthesia, Coulter possesses a rare neurological difference that blurs the lines between senses. For him, sound is not merely auditory — it is visual, immediate, and constant, with colours painting themselves across his field of vision with every note and noise. From a young age, he saw this experience not as metaphor but as literal reality, terrifying in its intensity but ultimately transformative.

His perception was not always a source of joy. As a child, the constant interplay between sensory inputs was disorienting. In parks, he lay on the grass and watched colour glide across the sky like iridescent oil. Even then, the experience was powerful, but difficult to articulate. Over time, however, he grew into it, gradually learning how to embrace and harness it. “It’s like walking now,” he has said — a part of life that’s so ingrained, it no longer feels strange. Today, Coulter channels this daily sensory overload into striking, large-scale paintings that capture not just what music sounds like to him, but how it looks, tastes, and feels. While some synaesthetes report subtle or occasional experiences, for Coulter, the cross-sensory storm is unrelenting, all-encompassing, and deeply embedded in his everyday consciousness.

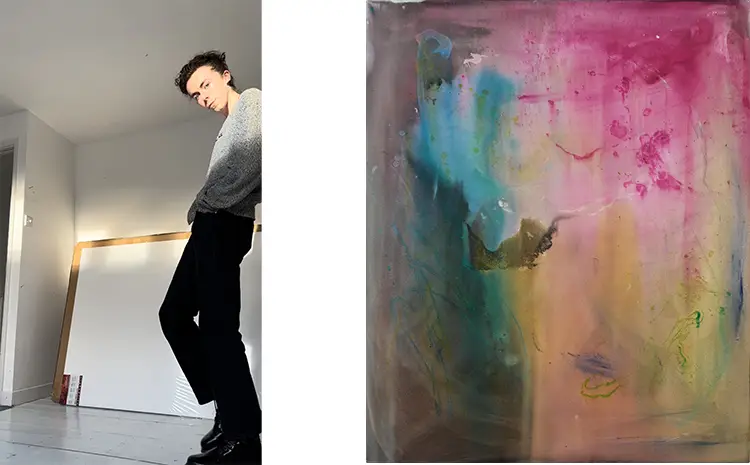

This gift — and burden — shaped his journey as an artist. He studied fine art at the University of Ulster and later moved to London, where his career began to gather momentum in unconventional ways. By the age of 21, he became the youngest artist to be acquired by the Arts Council Collection of Northern Ireland. From his humble beginnings painting on the floor of his garage, Coulter has built a reputation that reaches far beyond traditional art circles. His works have found homes with cultural icons such as Paul McCartney, Billie Eilish, and Elton John. Though his approach doesn’t fit the standard blueprint of an art career, it is precisely this divergence — his raw synaesthetic response to sound, filtered through instinct and emotion — that makes his output so captivating.

Jack Coulter: Synesthetic Visionary, Reluctant Showman

In a world where self-promotion and gallery alliances often define an artist’s rise, Jack Coulter remains a striking anomaly. Despite his international acclaim and high-profile collectors, he long resisted traditional solo exhibitions, feeling that they couldn’t fully encapsulate the layered, multi-sensory quality of his work. When he finally did agree to his debut solo show at Sotheby’s London — You Can’t Change The Music Of Your Soul — the format was unmistakably his own. Each canvas represented a specific piece of music and included a QR code linking the viewer directly to the corresponding song, reinforcing that these were not paintings inspired by sound, but rather, recordings of it through paint. The show’s follow-up in Dublin, A Song For You, drew even more attention, its emotional resonance intensified by the sudden passing of Sinéad O’Connor, whose song Nothing Compares 2 U inspired Coulter’s own favourite painting.

That particular piece — now featured on the cover of his new book — carries deep significance. “It cracked a code,” Coulter says, noting how people often cried while standing before it, listening to the song through headphones and absorbing the painting simultaneously. Such moments reaffirm his conviction that the work is not about style or trend but about truthful, emotional immersion. Coulter paints songs multiple times, sometimes creating several pieces for one track until one elicits a visceral, goosebump-level reaction — his personal litmus test for authenticity. It’s not a process of interpretation, he insists, but transmission. He enters the music completely, letting it move through him, producing work that is as much a performance as it is a product.

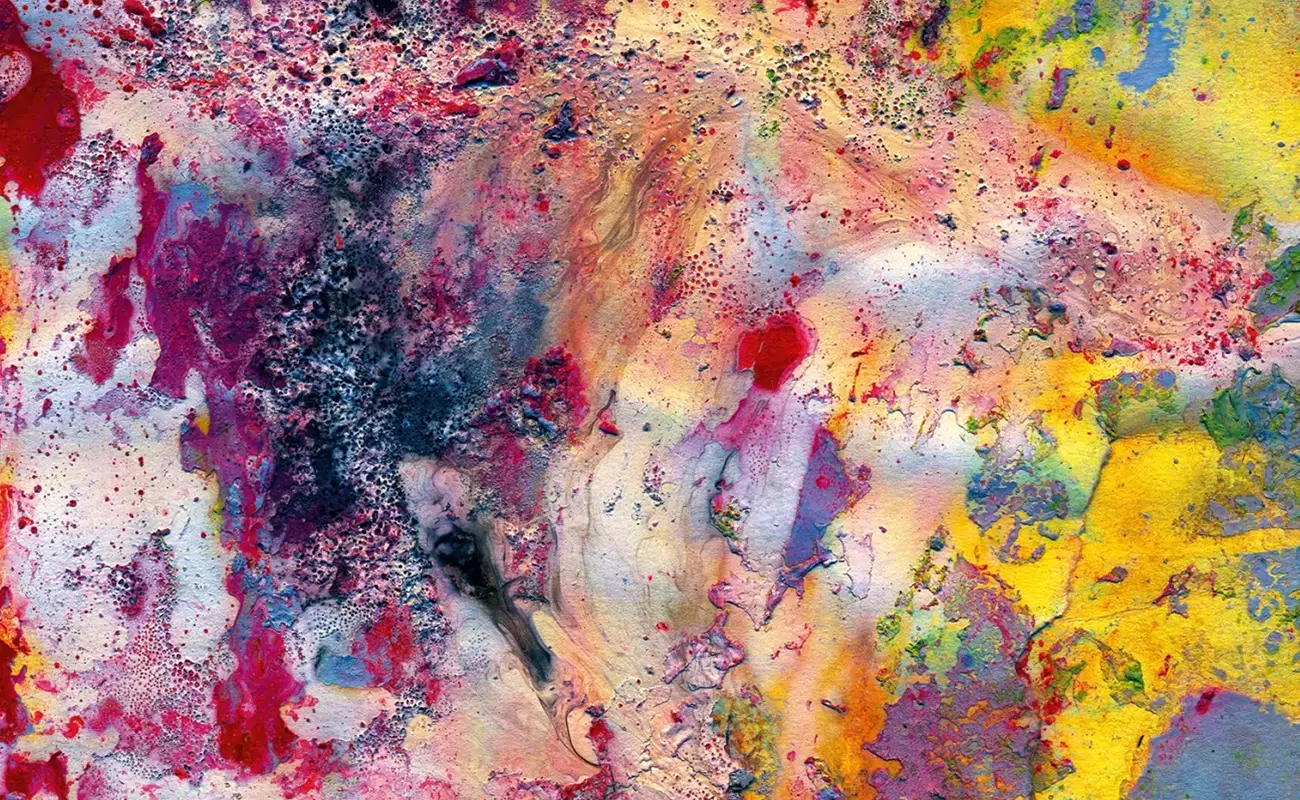

The performative aspect became central after his 2018 collaboration with the London Chamber Orchestra. During a live performance of Mendelssohn’s Violin Concerto, Coulter painted in real time — not in the spotlight, but hidden backstage, projected via livestream to a packed Cadogan Hall. The response was overwhelming, and the video amassed over two million views on Instagram. For him, the experience was nerve-racking but affirming. He realised then that painting could be more than solitary expression — it could be shared, enacted, and experienced as an unfolding event. Since then, the physicality and spontaneity of his process have become key to his allure. Whether pouring paint mixed with Coke or scraping pigment with CD cases, Coulter’s technique embraces chance, intensity, and immediacy. He often jokes about his unconventional tools and fears — “I thought the Coke might fizz on the canvas” — but the result is anything but haphazard. It’s intentional chaos, channeled with remarkable precision.

From Belfast Garage to Global Acclaim

Jack Coulter’s rise is remarkable not because it follows a fairy-tale arc, but because it breaks every rule of how success is supposed to look. His first studio was a garage in Belfast. His canvases were laid out on the floor, and instead of brushes, he used broken glass, discarded tools, or even his paint-splattered boots. Often, he mixed his own pigments using household items — gloss paint, fruit juices, vodka — creating works that are as chemically unstable as they are emotionally potent. This rawness is central to his appeal. Coulter is not interested in perfection, but in process, in capturing a fleeting, irreproducible moment. He treats painting like jazz: improvisational, responsive, and emotionally charged. His connection to music runs deep, from his early days listening to Miles Davis on his grandfather’s stereo to recent commissions that translate the tracks of Harry Styles, David Bowie, or Hans Zimmer into visually arresting compositions.

His audience has grown organically, largely through social media. Coulter has harnessed the power of Instagram to bypass traditional gatekeepers, sharing his work directly and candidly with followers around the world. That visibility has attracted a remarkable list of collectors, from musician Ben Lovett of Mumford & Sons to Queer Eye’s Antoni Porowski. Critics often point to the “vibrancy” and “balance” of his colours, but for musicians, the connection is more visceral. Many describe feeling as if the paintings evoke the same emotional landscape as the songs themselves. It’s no coincidence that Island Records, Abbey Road Studios, and even the Freddie Mercury Estate have turned to Coulter for visual interpretations of their most iconic material. His work offers something rare: not a narrative or a commentary, but a direct channel to feeling.

Despite this acclaim, Coulter remains modest about his trajectory. He manages his own career and is adamant that artists no longer need the structures of the past — no gallery, no manager, just vision and hard work. That philosophy has shaped every decision he’s made. He prefers authenticity to strategy, instinct over calculation. “The loneliest and most painful years of my life were those starting all of this,” he has said, reflecting on the sacrifices behind the spotlight. Now, with paintings selling for up to £40,000 and a waiting list of major collaborations, Coulter continues to reinvest in his practice. He sees his work not as an endpoint, but as an ongoing dialogue — with the sounds he hears, the people who listen, and the colours that refuse to leave him.

Jack Coulter: Sound as Emotion, Colour as Truth

Coulter’s body of work is shaped not just by the music he hears but by how it makes him feel — and that, in turn, is inseparable from how it appears in his mind’s eye. His approach is emotional first, visual second. Whether he’s working on Your Love by The Outfield or Almost (Sweet Music) by Hozier, his aim is not interpretation but immersion. He listens, relives past encounters with the song, and paints in real time. Often, he’s working on several pieces at once, toggling between tracks in an exhausting yet euphoric dance. One of his most poignant collaborations — with the late Shane MacGowan of The Pogues — yielded If I Should Fall From Grace With God, a dual-signed piece that reflects not only their shared Irish heritage but their mutual synaesthesia. MacGowan painted his section from a wheelchair, listening to Fairytale of New York and other Pogues songs. The finished work feels both personal and mythic.

Coulter’s favourite painting — his depiction of Nothing Compares 2 U — encapsulates everything his practice stands for. First exhibited during his Dublin show, the work quickly became a touchstone. Visitors stood before it with headphones on, weeping as they listened to Sinéad O’Connor’s haunting voice and absorbed the painting’s emotive weight. It’s that interplay between song and image, experience and memory, that makes Coulter’s work so resonant. Even the unexpected details — like a silhouette resembling Princess Diana in Candle in the Wind — seem to emerge organically, shaped by the emotional gravity of the music itself. Coulter insists he isn’t crafting tributes, but offering a direct translation of what he experiences. If it connects with others, it’s because they’re tapping into that same emotional current.

For all his innovations, Coulter retains a sense of wonder — even disbelief — about his journey. He speaks fondly of a moment when Elton John and his husband bought his painting of Candle in the Wind, calling it a “high point” in a career already filled with them. His book, which collects many of his most iconic works, has provided a moment of reflection. Coulter rarely slows down, but compiling the pieces allowed him to recognise the scope of what he’s built — not just a portfolio, but a visual record of feeling. His dream of recording his own music and painting to it still lingers in the distance. If that project comes to fruition, it would complete a feedback loop decades in the making: a boy hearing his heartbeat and seeing colour, now shaping both for others to witness.