Glenn Brown: Art as a Dream of the Subconscious

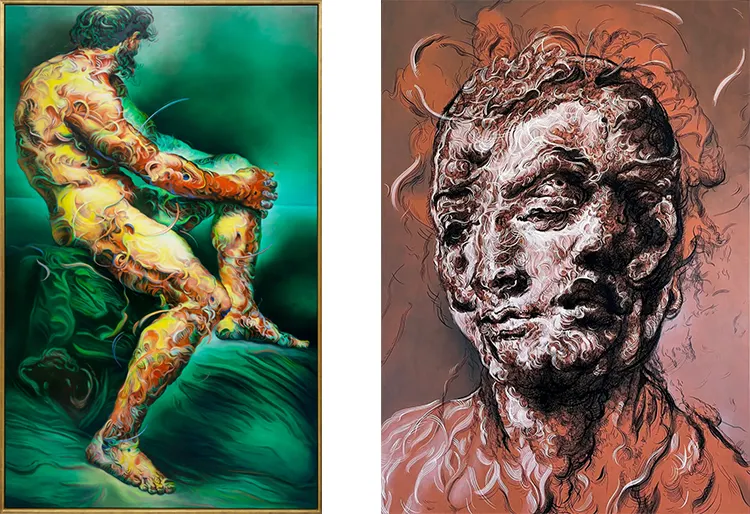

Glenn Brown’s work exists in an uncanny space where beauty and grotesqueness intertwine, creating images that feel both familiar and foreign. His paintings often appear as if they are pulled from a collective subconscious, a swirling mass of historical references and mutated forms. Brown has described his art as having “one foot in the grave,” evoking a sense of something neither fully alive nor entirely dead. His figures and compositions, while often sourced from art history, are stretched, distorted, and reimagined, forming unsettling yet mesmerizing visual experiences. This transformation of pre-existing imagery allows Brown to create works that appear timeless—simultaneously rooted in the past and hovering outside of it.

The eerie quality of Brown’s work stems from his fascination with the intersection of the beautiful and the grotesque. His paintings often depict figures with exaggerated features, elongated limbs, or faces that seem to dissolve into amorphous shapes. While these images may evoke classical portraiture or Baroque compositions, they carry a nightmarish quality, as if viewed through the distortion of memory or a dream. Brown likens his approach to the way the mind processes images in sleep—constantly merging, mutating, and reforming. His paintings refuse to settle into a single, stable identity, instead offering an experience of visual flux that unsettles and fascinates in equal measure.

This liminal quality is central to Brown’s artistic philosophy. He resists the notion of fixed meaning, preferring to create works that exist in a state of perpetual transformation. By engaging with historical images in a way that stretches their original intent, he disrupts their stability, inviting viewers to reconsider the boundaries between past and present, between what is remembered and what is imagined. His paintings, often hovering between the realms of classical elegance and unsettling distortion, challenge our expectations of art and perception, making us question where recognition ends and invention begins.

Glenn Brown: Appropriation, Transformation, and the Weight of Art History

Brown’s deep engagement with art history is one of the defining characteristics of his work. Rather than treating historical paintings as fixed artifacts, he sees them as living entities—mutable, open to reinvention, and capable of new interpretations. His process of appropriation does not involve direct replication; instead, he takes existing images and subjects them to intense manipulation. Colors shift unpredictably, proportions warp beyond recognition, and emotional tones are completely reimagined. By distorting and recontextualizing these images, Brown creates works that acknowledge their historical lineage while breaking free from it, transforming them into something that belongs to no single time period.

This approach has not been without controversy. Some critics and artists have accused Brown of veering too close to plagiarism, questioning whether his manipulation of historical paintings constitutes a true act of creation. Brown, however, firmly rejects such accusations, arguing that his work is rooted in transformation rather than mere replication. He points to the long history of artistic borrowing and reinterpretation, noting that painting itself has always been an evolving conversation across generations. His compositions are often hybrids, incorporating multiple sources at once, blending them into forms that bear little resemblance to their origins. The end result is not a simple appropriation, but rather a complete reinvention—one that challenges the very nature of originality in art.

For Brown, the past is not a fixed entity but a reservoir of images waiting to be reshaped. His work engages in a dialogue with the masters of previous centuries, yet it resists nostalgia. Instead of preserving history, he fractures it, stretching and contorting its visual language into something unrecognizably new. His paintings exist in a space that is neither entirely historical nor fully contemporary—timeless yet unstable, familiar yet utterly alien. By continuously reshaping art history through his lens, Brown ensures that the past remains in motion, never settling into a singular narrative but constantly evolving in unexpected ways.

The Illusion of Texture: Painting in the Digital Age

A defining feature of Brown’s paintings is their illusion of texture. At first glance, his works appear to be thick with impasto, their swirling brushstrokes seemingly built up into sculptural layers of paint. Yet upon closer inspection, their surfaces are impossibly smooth, devoid of the physical weight that the eye expects. This contradiction between appearance and reality plays a crucial role in his artistic philosophy. By meticulously mimicking the look of impasto while keeping his surfaces flat, Brown disrupts the viewer’s sensory expectations, forcing them to engage with the painting in a new way.

This illusionistic quality is closely tied to Brown’s use of digital technology. Before beginning a painting, he manipulates images on a computer, experimenting with distortions, recombinations, and color shifts. This allows him to push the transformation of an image far beyond what traditional sketching methods might permit. However, despite this embrace of digital tools, Brown remains committed to the physical act of painting. He sees oil paint as possessing an almost alchemical power—something capable of capturing the ineffable, something that technology alone cannot replicate. His work ultimately exists in the tension between the digital and the handmade, between technological manipulation and the ancient craft of painting.

The visceral impact of Brown’s paintings extends beyond the purely visual. Many viewers report feeling a desire to touch—or even taste—the swirling forms, as if they are tantalizingly close to being tangible. This reaction underscores the sensory ambiguity of his work, where texture is simultaneously present and absent. The paintings create a space of contradiction, where the eye believes in substance, but the hand would find none. By subverting our expectations of materiality, Brown forces us to reconsider our relationship with painting itself, questioning not only what we see, but how we experience art on a physical level.

Glenn Brown: Sculpture, Drawing, and the Expansion of Artistic Language

While Brown is primarily known for his paintings, his practice has expanded into sculpture and drawing, each medium offering new ways to explore the ideas at the core of his work. His sculptures, for instance, represent a radical inversion of his paintings’ illusionistic flatness. Instead of creating the appearance of thick paint while keeping the surface smooth, his sculptures make the brushstroke fully three-dimensional. Built from layers of oil paint over existing bronze figures, these works exaggerate texture, making the paint itself a sculptural element. By doing so, Brown transforms the ephemeral gesture of a brushstroke into something solid, something physically present in space.

His early sculptures were deliberately placed on the gallery floor, appearing as if they had collapsed out of a painting, rejecting the traditional pedestal. However, the fragility of these works led Brown to eventually enclose them in glass vitrines. This shift not only protected them but also introduced a new dynamic—an interplay between containment and exposure. Encased in glass, the sculptures take on an almost scientific quality, as if they are specimens preserved for study. This containment adds to their uncanny nature, reinforcing the idea that Brown’s work exists in a state of perpetual transformation, never fully belonging to one realm or another.

In recent years, drawing has become an increasingly vital part of Brown’s practice. Inspired by Old Master sketches, he incorporates their gestural energy into his own works, layering multiple historical images atop one another to create compositions that pulse with movement. His drawings, much like his paintings, resist fixed identities, instead presenting figures and forms that dissolve and reform before the viewer’s eyes. By engaging with drawing as a primary medium rather than simply a preparatory tool, Brown continues his exploration of the shifting, unstable nature of images, demonstrating that the act of transformation is not confined to any one medium, but is the very foundation of his artistic vision.