“I tend to see the world in black and white. For me, a person and a building are inseparable: people shape spaces, and spaces shape people.”

Structures with a Soul: Tracing Memory Through Shape and Shadow

Architecture and identity are not distant ideas in the work of Barbara Schwinges. For her, they are intimately bound — the walls that surround us are as expressive as the words we use. From the stark silhouettes of coal mines to the fluid elegance of calligraphy, Schwinges creates a visual dialogue between people and the places they inhabit. Her art captures the reciprocity between human presence and constructed space, using abstraction to reduce form to its most powerful essence. Working exclusively in black and white, she distills buildings and faces alike into a language of contrast, line, and emotion, transforming physical structures into psychological landscapes.

Growing up in Oberhausen, in Germany’s industrial Ruhr region, Schwinges was shaped by the shifting contours of a post-industrial society. Her father’s work in power plant construction introduced her early on to the aesthetics of engineering, while her mother nurtured her love for clarity and form in written expression. The collapse of the steel industry and the social upheaval it left behind were not just economic events but visual and emotional milestones. These dual legacies — technical structure and expressive writing — became the twin anchors of her practice. Her early role as a technical draftswoman laid the groundwork for her unique use of line and space, giving her the precision and confidence to engage deeply with minimalist form.

Later studies in visual communication led Schwinges to explore how drawing, design, and calligraphy might converge. The rigor of technical drawing informed her clean compositional language, while calligraphy opened a channel for personal rhythm and reflection. Her current work draws from these foundations and continues to evolve through exhibitions, commissions, and independent projects. Now based in Unkel, a town steeped in cultural tradition along the Rhine, she continues to create work that bridges the external and internal, the built and the imagined, all while expanding her dialogue with architecture, language, and the human condition.

Barbara Schwinges: Writing the Image, Imaging the Word

Calligraphy, for Schwinges, is not an embellishment but a fundamental act of expression — a medium through which thought, form, and identity can converge. She was first introduced to this powerful art form during her design studies, but it was her mentorship with renowned calligrapher Professor Werner Eikel that profoundly altered her path. He encouraged her to turn inward, to use calligraphy not simply to adorn but to articulate. In her hands, the act of writing becomes a visual exploration of character and presence, where letters serve not only as linguistic units but as emotional gestures. A pen and nib become tools of introspection, translating inner states into tactile, visual forms on paper.

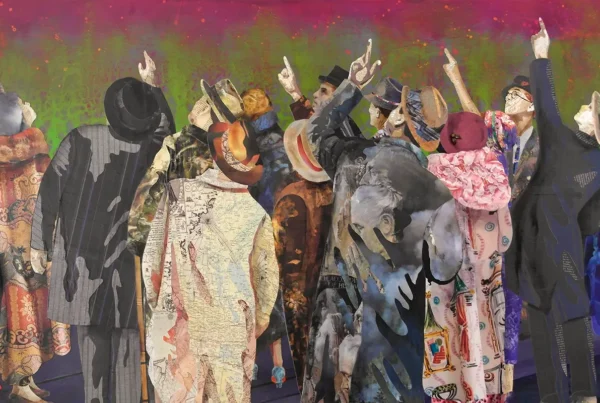

Among her most distinctive works are her calligraphic portraits — intimate, word-based representations of historical and contemporary figures. These are not traditional likenesses but rather layered interpretations in which text becomes image. Figures like Willy Brandt, Ruth Bader Ginsburg, Frida Kahlo, and Greta Thunberg emerge not through shading or photorealism but through the careful shaping of their own words. In these portraits, Schwinges allows each subject to “write” themselves into being, using their thoughts and visions as the raw material of their image. There is no gradation, only pure contrast: light and shadow etched with the fluid movement of language. These pieces invite viewers to read as much as they look, engaging both eye and mind in an act of simultaneous perception.

This interplay of written language and visual form is extended in series such as A Hat Comes Around the Corner and Those Who Don’t Want to Think Get Kicked Out, where she examines the evolution of Joseph Beuys from man to myth. The script she chooses for each stage in his life mirrors the emotional and artistic transformation he underwent. Early works appear delicate, reflecting Beuys’s initial sensitivity, while later depictions adopt a coarser, more angular rhythm, culminating in the iconic hat that became his symbolic signature. By adapting her script to echo the character and trajectory of her subjects, Schwinges builds a multi-sensory portrait — one that is as much about inner essence as it is about external likeness.

Where Architecture Breathes: Drawing Through Movement and Memory

Barbara Schwinges approaches buildings not as static entities but as living presences filled with psychological weight. Her architectural drawings are less about representation and more about revelation — the uncovering of emotional resonance through spatial investigation. Her process begins with a freehand sketch, done without the aid of rulers or digital tools, establishing an intimate physical connection with the structure. But the real work begins when she mentally inhabits the space, asking what the building feels like, how people move through it, and how its form shapes behavior. Her drawings become responses — both hers and those of the people within the space — translated into a vocabulary of lines, surfaces, and shifting light.

Public buildings are a recurring focus in her portfolio. Hospitals, churches, museums, and industrial ruins all become sites of inquiry into how space impacts human experience. For Schwinges, architecture is deeply personal and socially charged. A church might evoke reverence or unease; a demolished factory might echo with past lives and lost identities. Her minimalist approach does not seek to recreate these buildings in detail, but rather to convey their emotional footprint. This is evident in works such as Being and Time, based on Hamburg’s Elbphilharmonie, where she charts the building’s layered interaction with the people who visit it. Light, shadow, and architectural rhythm merge with human presence, capturing both the physical structure and the lived experience within.

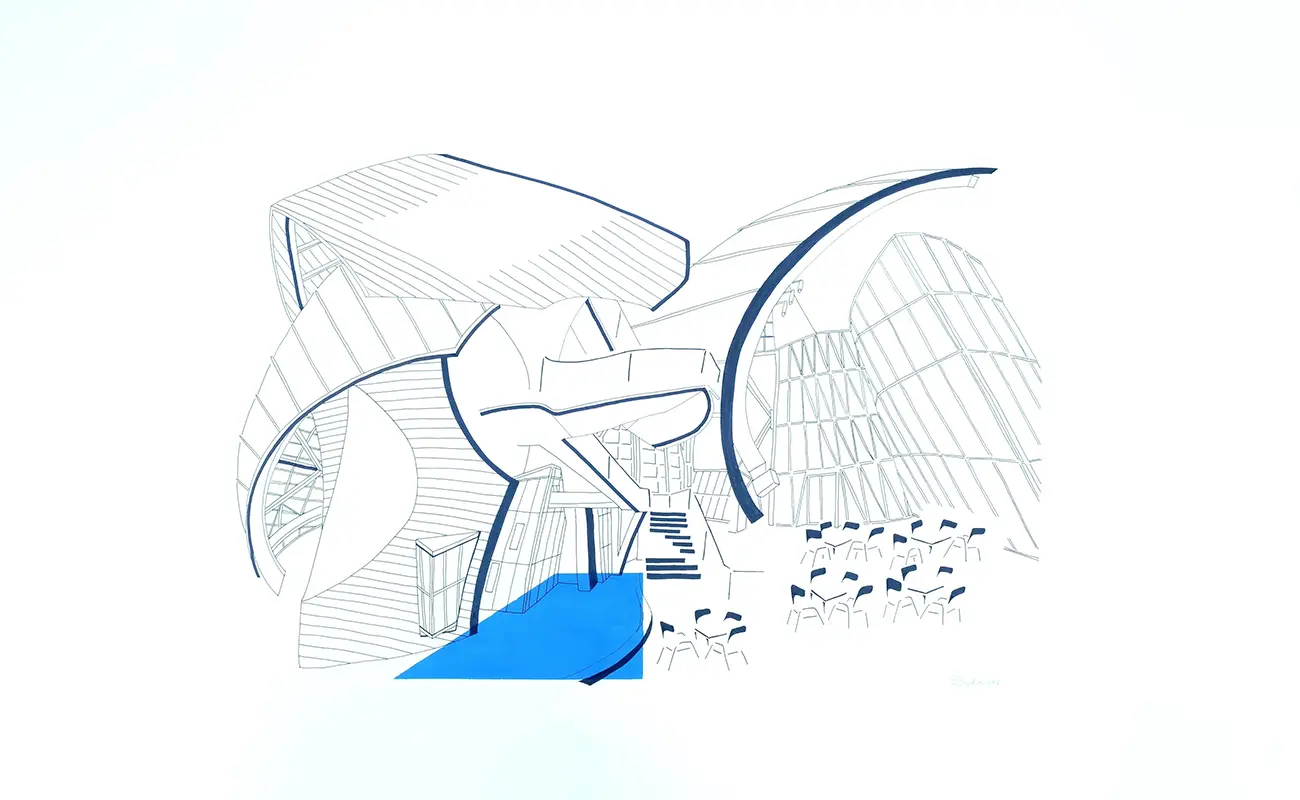

Her project Sensory Spaces, centered on Frank Gehry’s Fondation Louis Vuitton, exemplifies the immersive quality of her process. She interprets the building as a dynamic voyage, likening it to ships circling an iceberg. Beginning with exterior perspectives, she gradually moves inside, carefully observing the way people navigate its spaces. Drawing each facet until she feels entirely familiar with its contours, Schwinges internalizes the structure until it becomes a part of her. From there, she reconstructs it through intuitive lines, shifting between perspectives, dissolving boundaries between inside and out. The result is a spatial experience rendered in two dimensions, yet pulsing with the energy of movement, reflection, and sensory memory.

Barbara Schwinges: The Architecture of Uncertainty

What distinguishes Schwinges’s artistic method is her refusal to settle into predictability. Although her work often emerges in extended series — sometimes comprising up to 50 pieces — each new drawing prompts a reassessment. The architecture she draws does not allow for formula; each structure demands a new entry point, a different rhythm, a fresh arrangement of lines and voids. As she begins, she frequently finds herself compelled to shift directions, scrap assumptions, and allow the piece to evolve organically. This cycle of questioning, releasing, and rebuilding lies at the core of her creative process, one that resists routine and embraces the uncertainty inherent in artistic inquiry.

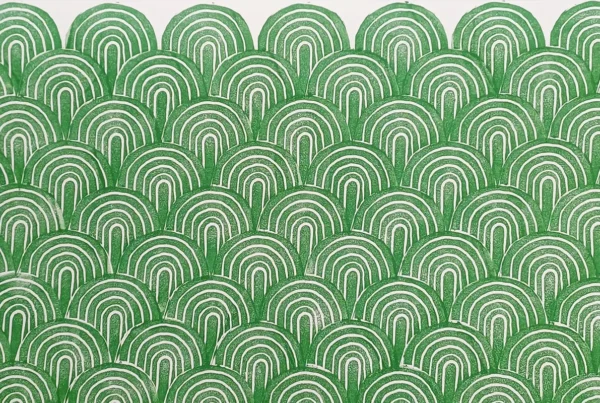

Working on large-scale formats, often 100 × 70 cm or more, Schwinges finds a physical freedom that matches her conceptual one. The increased scale enables her to explore the gestural potential of calligraphy and the spatial complexity of architecture simultaneously. With tools as simple as ink, marker, and brush, she fragments and reconstructs forms, introducing color fields that evoke natural elements like sky, water, or vegetation without directly illustrating them. These abstract planes of color serve to contextualize the structures, or occasionally to dissolve them entirely, allowing her drawings to hover between realism and abstraction, between documentation and interpretation.

Despite forays into painting, sculpture, and installation, her work continually returns to the written line — not just as a form of writing but as a core vehicle for perception. Whether she is drawing the outline of a building or tracing a calligraphic arc, the gesture itself becomes a site of meaning. In Schwinges’s world, form is never just formal. It is a way of thinking, of feeling, of making sense of how people inhabit space and how space, in turn, inhabits them. Through her evolving visual language, she offers viewers an invitation: to see with greater clarity, to read between lines, and to recognize the architecture that shapes not just cities, but lives.