“I am interested in a political art, that is to say an art of ambiguity, contradiction, uncompleted gestures and uncertain ending – an art (and a politics) in which optimism is kept in check, and nihilism at bay.”

The Landscape of Influence: Johannesburg’s Imprint on William Kentridge’s Art

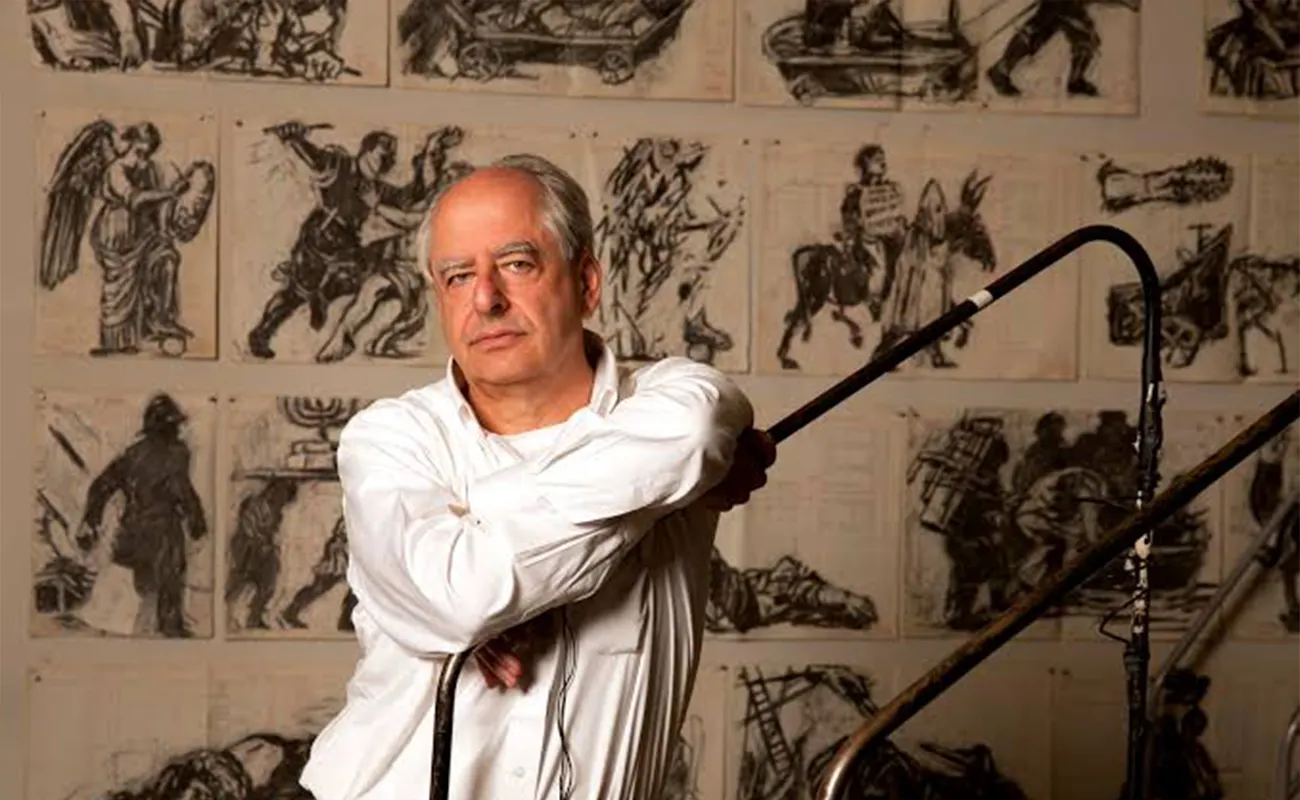

William Kentridge, born in 1955 in Johannesburg, South Africa, grew up amidst the oppressive shadow of apartheid, an era that profoundly influenced his artistic journey. Coming from a Jewish family deeply entrenched in the pursuit of justice, with both parents serving as lawyers defending marginalized individuals, Kentridge’s upbringing was steeped in the socio-political tensions of his homeland. While he did not actively participate in the struggle against apartheid, his position as an observer of its complexities became a critical foundation for his creative work. This duality—of empathy and critique—imbues his art with a sense of engagement that bridges personal experiences with broader historical narratives.

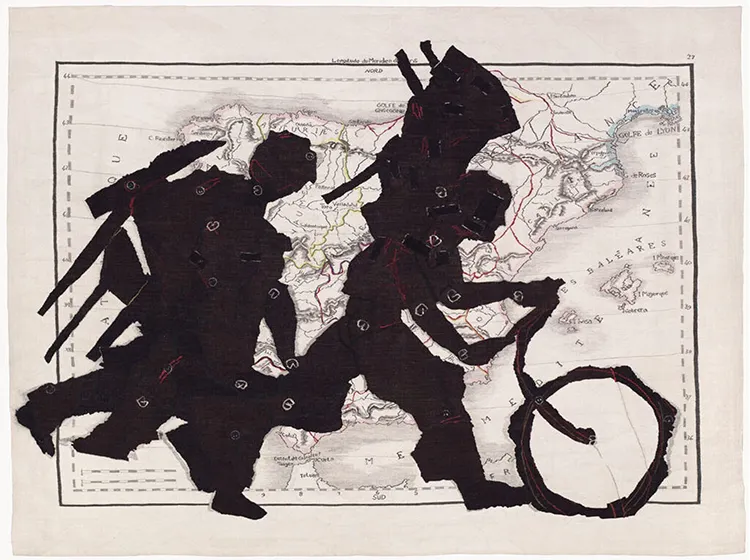

Johannesburg’s urban environment, a vibrant yet fractured city, serves as both a muse and a canvas for Kentridge. His work reflects the city’s dichotomies—its harsh inequities and unyielding resilience. This setting provided him with a dynamic lens through which to explore themes of power, loss, and identity. Kentridge sees Johannesburg not just as a physical location but as a palimpsest of histories, where the past and present collide, shaping his unique approach to storytelling through art.

By grappling with the societal dynamics of Johannesburg, Kentridge has developed an oeuvre that refuses simplification. His art doesn’t merely depict apartheid-era injustices; instead, it dissects and reconstructs fragments of memory, challenging the viewer to confront the contradictions of history. Through his intricate explorations, he transforms his birthplace into a universal metaphor for humanity’s collective struggles and triumphs.

William Kentridge: The Art of Erasure and Reclamation

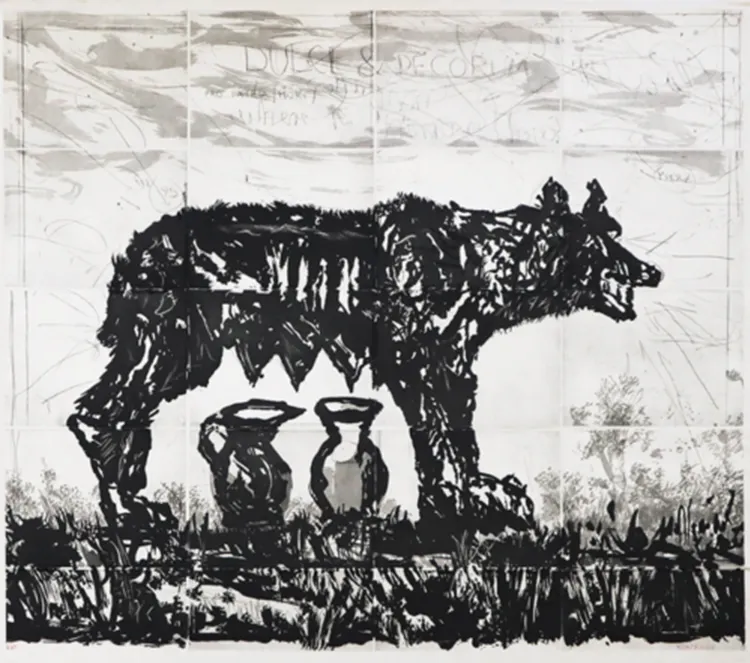

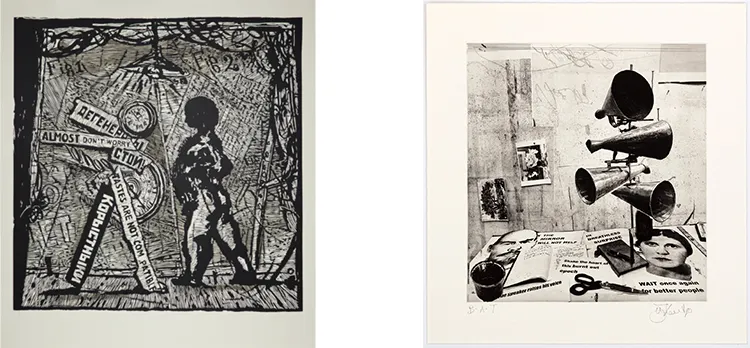

Kentridge’s distinctive approach to animation—built on a technique of erasure and redrawing—exemplifies his philosophy of art as a medium of transformation. Working with charcoal on paper, he creates and alters images on a single sheet, filming each iteration to produce a sequence that becomes a visual palimpsest. This process, which leaves behind traces of previous marks, mirrors the fragmented and layered nature of memory. It’s not about obliteration but about acknowledging the persistence of what lingers, the echoes of what came before.

This technique reflects his fascination with the dualities of remembering and forgetting. For Kentridge, memory is inherently messy—layered with contradictions, omissions, and remnants of the past. His animations, therefore, become metaphors for the human experience, where no single narrative dominates but instead coexists with others in an intricate web. This layered methodology also critiques the notion of linear historical narratives, proposing instead that history is constructed from overlapping, often conflicting, fragments.

His acclaimed series, 9 Drawings for Projection, created between 1989 and 2003, illustrates this philosophy vividly. Through the recurring characters of Soho Eckstein, a capitalist tycoon, and Felix Teitlebaum, a more introspective alter ego, Kentridge examines the personal and societal upheavals during South Africa’s transition from apartheid to democracy. These animations serve as a poignant meditation on power, guilt, and the complexity of reconciliation, their layered visuals underscoring the unresolved tensions of a nation in flux.

Intertwining Mediums: From Charcoal to Opera

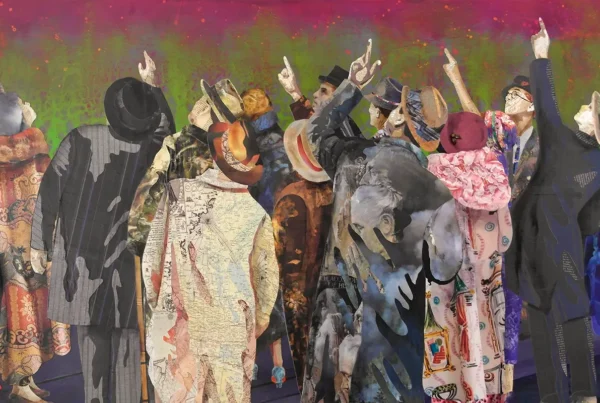

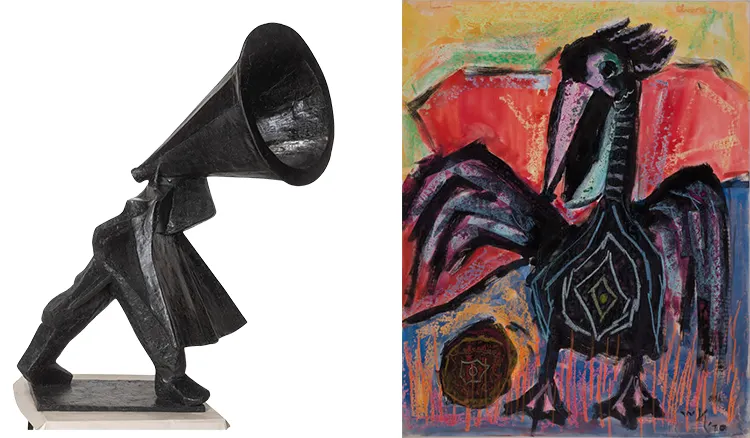

Kentridge’s artistic repertoire spans an impressive array of mediums, including drawing, film, opera, and sculpture, each chosen not for its novelty but for its capacity to amplify the ideas driving the work. For Kentridge, the medium is a vessel rather than a destination, with each form offering distinct possibilities and constraints that shape his creative process. The tactile immediacy of charcoal drawings allows for a raw exploration of ideas, while the operatic stage provides a multidimensional platform for combining visual, musical, and performative storytelling.

His ventures into opera, such as his direction of Wozzeck and Lulu, reveal how the theatrical realm informs his visual art. The temporal, spatial, and auditory dimensions of opera resonate with the layered, time-based nature of his animations. Both disciplines invite audiences to navigate multiple perspectives simultaneously, fostering a richer engagement with the work’s themes. These experiences underscore Kentridge’s belief in art as a collaborative endeavor, where the interplay of different voices and disciplines generates new avenues of discovery.

Projects like Triumphs and Laments along Rome’s Tiber River exemplify his ability to merge concept and form. This 550-meter frieze, created by erasing layers of grime to reveal fleeting images, is a meditation on impermanence, celebrating and lamenting human history. The work’s ephemeral nature reinforces Kentridge’s preoccupation with memory’s fragility and the inevitability of loss, themes that permeate his entire body of work.

William Kentridge: Collaboration and the Imperfections of Process

Collaboration occupies a central role in Kentridge’s artistic philosophy, extending across his operatic productions, theatrical performances, and visual artworks. Whether working with musicians, designers, or performers, he views collaboration as an enriching dialogue that challenges his perspectives and enhances the final creation. This collective dynamic mirrors his thematic focus on ambiguity and contradiction, as diverse voices converge to form a cohesive yet multifaceted whole.

Equally integral to Kentridge’s practice is his embrace of imperfection and the unpredictability of the creative process. For him, the studio is not a space of certainty but one of exploration, where meaning emerges through the act of making rather than through preordained concepts. He celebrates the serendipity of mistakes and the provisional nature of creation, viewing them as essential to the authenticity of the work. This approach, rooted in process rather than product, aligns with his broader critique of rigid narratives, emphasizing instead the fluidity of interpretation.

Ultimately, Kentridge invites audiences into a space of reflection, where the complexities of history, identity, and memory can be engaged with on their own terms. His art resists easy answers, offering instead a tapestry of experiences that resonate with the shared uncertainties of human existence. By embracing the provisional, the layered, and the collaborative, Kentridge redefines art as a dynamic dialogue between the past and the present, the individual and the collective.