“Art is a painkiller for those who suffer. It is the ultimate expression of imagination through compassion: when someone suffers, you suffer together.”

Exile and Expression: A Dual Voice in Paint

In the heart of London, far from their native Hong Kong, Lumli and Lumlong have forged an artistic path as a married couple co-creating politically charged oil paintings. Both artists were born into working-class families and later pursued fine art studies in France, a formative experience that continues to shape their work. Since fleeing Hong Kong in 2021 amid escalating political repression, their art has become a powerful act of cultural preservation and resistance. Their paintings echo the traumas of displacement and the urgency of safeguarding freedoms once taken for granted. Despite the upheaval in their lives, their shared creative practice remains rooted in intimacy, with Lumlong working on the left side of each canvas by day and Lumli completing the right side by night.

Their work has drawn international attention, having been shown in prestigious venues across London, Paris, Berlin, and New York, as well as in the European and UK Parliaments. Lumli and Lumlong have also exhibited in national museums and received critical coverage in outlets such as The Times, The Sunday Times, AFP, and ZDF. Recognition for their unflinching artistic voice continues to grow — they have been selected to participate in the London Art Biennial 2025. While their artistic themes explore broad global issues, their lived experience infuses each painting with visceral authenticity. Working in exile, they have harnessed their creative process not only as a form of expression but also as an act of defiance and cultural memory.

Despite the gravitas of their themes, the origins of their artistic journeys are rooted in childhood moments of scarcity and wonder. Lumli recalls drawing on discarded drink cartons to mimic the stationery she couldn’t afford — a modest beginning that sparked a lifelong commitment to artistic storytelling. For Lumlong, creativity was embedded in family life. He remembers watching his father draw birds with such lifelike elegance that it seemed the pen held magical power. These early encounters with art grew not just from passion but from necessity. In their words, poverty acted as a catalyst: when material things were absent, imagination stepped in. Art was not a luxury — it was a way of seeing, of coping, and ultimately, of surviving.

Lumli Lumlong: Painting Truths Too Loud to Ignore

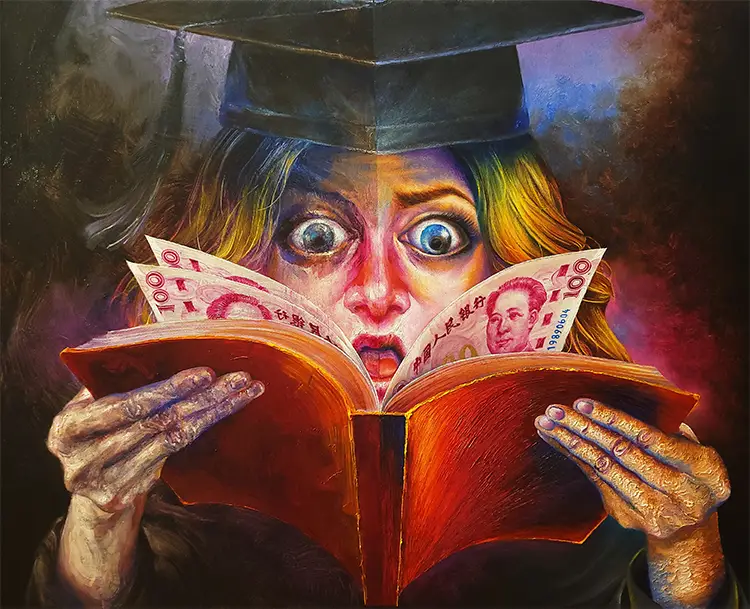

Stylistically, Lumli and Lumlong are known for their grotesque oil paintings, a term they use not in the sense of horror for its own sake, but as a means of confronting viewers with harsh social realities. Their compositions often focus on marginalized communities — the impoverished, the disabled, rural workers — and extend to broader human rights themes like war, exile, and freedom of speech. Much of their work responds directly to the sociopolitical upheaval in Hong Kong, using visual storytelling to preserve a cultural identity now under threat. Their art is both a document and an outcry — a vivid portrayal of what it means to resist forgetting in the face of forced erasure.

The grotesque, in their hands, becomes a tool for empathy. “Art never lies,” they say, insisting that even the most surreal imagery is anchored in truth. In their view, reality itself can be more disturbing than the darkest painting. Through symbolic distortions and dramatic expressions, they offer visual metaphors that mirror society’s injustices. Yet their goal is not to shock, but to connect. They describe art as a “painkiller” — not a cure for suffering, but a companion to it. With every canvas, they aim to become the voice of those who are often ignored. Their work becomes a silent yet thunderous solidarity with the dispossessed, carrying a deep emotional resonance through every brushstroke.

Among their most significant pieces is Thousand Hands Man, a tribute to the 2019 Hong Kong social movement. Inspired by the Buddhist bodhisattva Thousand-Hand Guanyin, the figure in the painting wields symbolic objects instead of weapons. His multitude of arms — all part of one unified body — represents solidarity across ideological lines within the movement. The imagery also references Bruce Lee’s metaphor “be water,” with water bottles replacing nunchaku to embody adaptability and resilience. Beneath the figure’s legs lie the spirits of deceased activists, adding a solemn, spiritual layer to the composition. During the painting process, they listened to a self-proclaimed medium who shared alleged visions of those spirits. One evening, they experienced strange electrical surges and a burnt-out bulb, which moved them to tears rather than fear. This intense moment deepened the emotional connection to their work, blurring the lines between memory, mourning, and myth.

Symbols of Resistance and Solitude

Their creative process unfolds within the tight confines of a small London studio, where space constraints contrast starkly with the scale of their works, some towering over two metres in height. Despite the physical limitations, they embrace the challenge, seeing it not as a barrier but as part of the journey. What proves more difficult is the emotional toll of their artistic direction. Their chosen style — stark, symbolic, and unflinchingly political — often sits outside popular trends. This disconnect from mainstream tastes has led to a persistent sense of artistic loneliness. Creating in the margins, they acknowledge that success as socially engaged artists requires a continuous reckoning with rejection and isolation.

Still, their commitment to their vision remains unwavering. The tension between internal conviction and external reception becomes part of the work itself. Art, for them, is not about aesthetic pleasure or market success; it is a personal and political imperative. When confronting subjects such as war, displacement, and repression, they do not dilute their message for accessibility. Instead, they lean into the discomfort, inviting audiences to grapple with complex truths. Their studio may be modest, but the emotional and symbolic scope of what they produce knows no such bounds. Every canvas serves as a battleground between silence and speech, suffering and resistance.

From a materials standpoint, oil paint is not just a medium — it is a passion. Both artists began using oils in their early twenties after experimenting with other tools like charcoal and watercolor. The texture, saturation, and slow drying time of oil paints allow for intricate layering and atmospheric effects, giving them the freedom to manipulate tone and detail with nuance. They describe a deep love for the earthy scent of the paint and the tactile pleasure of working with it. Though oil is often considered difficult to master, its challenges are part of its allure. The medium’s physicality mirrors the intensity of their themes — complex, layered, and stubbornly real. While they’ve explored other forms, oil painting remains their chosen language, one that matches the weight of the stories they choose to tell.

Lumli Lumlong: Across Deserts, Across Divides

The power of their artistic message has not gone unnoticed by organizations that see in their work a capacity to spark meaningful dialogue. One such opportunity is on the horizon: an invitation to create a massive seven-metre-wide mural in the American desert. Focused on the theme of human rights, this project has been a year in the making, with logistical and financial preparations now reaching a critical point. For Lumli and Lumlong, the prospect of painting in such a harsh, expansive landscape presents a profound challenge — both physically and emotionally. Yet they welcome it as a rare chance to bring their art into a new context, one where its message might ripple outward across vast, open land.

The mural is envisioned as more than an artwork; it is conceived as a declaration. It will not hang in a gallery or museum, but live beneath the same sky that shelters protestors, refugees, and forgotten communities worldwide. The couple views this project as a bridge — between continents, between viewers and the voiceless, and between the personal and political. In a space where time slows and distractions vanish, they hope their work will resonate not just through imagery but through presence. The desert becomes a canvas, and the mural becomes a statement: resistance cannot be contained.

This project also marks a continuation of their enduring theme — art as witness. Whether painted in a cramped London studio or stretched across an American desert, their creations speak of lives disrupted, voices silenced, and truths buried. Through deeply personal narratives and universally resonant symbols, Lumli and Lumlong assert that art is not merely a reflection of society but an instrument for reshaping it. Their work is as much about preserving memory as it is about igniting conscience. Every project, every painting, and every public display becomes a thread in a larger act of remembering and resisting — a legacy built in brushstrokes and belief.